Université de Picardie-Jules-Verne (Amiens)

Colloque international « Poétique du roman choral »/« Poetics of the Choral Novel »

Le Logis du Roy (Amiens), 26 et 27 septembre 2024

English version below

L’adjectif « choral » a été emprunté à la critique cinématographique pour être appliqué à la littérature : si l’étiquette est commode, et a connu un certain succès marketing et médiatique, le roman choral n’a pas fait l’objet de tentative de définition précise. Il conviendra donc de s’interroger sur la pertinence de la notion, son histoire – et aussi sa métaphorologie. Outre celle du chœur, musical ou tragique, qui méritent un examen particulier, les métaphores convoquées pour dire l’œuvre chorale devront faire l’objet d’une étude attentive : « mosaïque », « kaléidoscope », « puzzle » ; « braided plot », « crossway stories », « network narratives », etc. Parallèlement, l’effort de définition de la singularité de la choralité pose la question de la place de l’œuvre chorale – ou des caractéristiques mises en avant par le choix de l’adjectif – dans une constellation plus large des notions et des catégories génériques qui lui sont associées : « dialogisme », « polyphonie », « plurivocalité », « hétéroglossie » ; « roman pluraliste », « livre de voix », « roman maximaliste », etc.

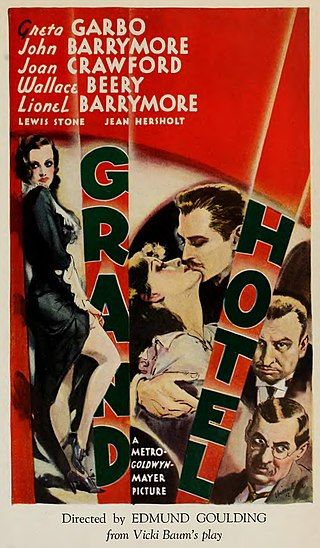

Il conviendra également de s’intéresser au moment d’émergence, ou de cristallisation, du genre. Aldous Huxley publie en 1928 Point Counter Point. Menschen im Hotel. Kolportageroman mit Hintergründen (1929, Vicki Baum) est adapté dans la foulée au cinéma (Grand Hotel, 1932, Edmund Goulding). As I Lay Dying (William Faulkner) paraît en 1930, peu après Perrudja (1929, Hans Henny Jahnn), qui est contemporain de The Sound and The Fury (1929), et deux ans plus tard Virginia Woolf fait paraîtreThe Wawes (1931). Il faudrait aussi citer Manhattan Transfer (1925, John Dos Passos) – habituellement considéré comme un roman de montage. Et aussi Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929, Alfred Döblin), sans oublier l’incontournable Ulysses (1918-1920/1922) de James Joyce.

Proposons, par hypothèse et en première approximation, qu’une œuvre chorale se définisse par trois caractéristiques :

- elle met en scène une mosaïque de personnages et donne à entendre une pluralité orchestrée de voix singulières et subjectives, qui alternent. Dans le roman choral, chacun des personnages-narrateurs est ainsi défini par ses paroles et/ou ses pensées, dont les caractéristiques idiosyncrasiques, idio- ou sociolectales, font l’objet d’un investissement particulier,

- elle entrelace des lignes narratives différentes. Le récit se compose d’histoires multiples et entrecroisées, qui suppose à la fois l’indépendance, plus ou moins marquée, des histoires et des points de convergence, de rencontre ou de croisement, qui peuvent être actualisés dans la fiction ou bien relever de l’interprétation. Délinéarisant la chronologie narrative, il agence les événements selon une composition tabulaire, qui favorise, par des jeux de recoupement ou de recouvrement, des associations, locales ou à plus grande échelle, par échos et résonances,

- elle propose une représentation plurisperspectiviste de la réalité. La combinaison des points de vue permet, non pas d’élargir le point de vue, mais de cerner progressivement, et de façon idéalement synoptique, un événement/personnage/objet central – qui est souvent une tache aveugle. Le roman choral est donc fondé sur une tension entre restriction du point de vue et une tentative symétriquement inverse de pallier cette constriction myopique par une représentation kaléidoscopique, facettée ou mosaïque.

Il conviendra d’étudier la pertinence de cette première définition, tout en en affinant les critères pour proposer une typologie opératoire des différentes formes d’œuvre chorale. On pourrait ainsi distinguer :

a) les récits dans lesquels les personnages-narrateurs – qui sont souvent des témoins – présentent successivement leur point de vue (leur vision, leur interprétation) sur/d’un même événement/personnage/objet (l’unité est d’action).

b) les récits dans lesquels les personnages-narrateurs se connaissent/se croisent/se rencontrent sans que les perspectives soient unifiées par un événement commun (l’unité est avant tout de lieu : port, gare, hôtel, café, village, immeuble, tour, voire cimetière, etc.).

c) les récits dans lesquels les personnages-narrateurs n’ont aucun lien/lieu en commun.

On peut distinguer en outre une version optimiste et pessimiste de la choralité, selon que la multiplication des points de vue permet de reconstituer l’objet absent, ou perdu, ou que la tentative échoue, soit par lacune, soit par contradiction interne de points de vue qui n’arrivent pas à s’accorder. Il conviendrait peut-être d’ajouter une troisième catégorie, intermédiaire, où l’événement perçu fait l’objet d’une perception décalée, d’un décentrement de perspective, mais qui ne porte pas atteinte à la cohérence de l’image mosaïque.

La typologie pourra encore s’affiner par variation incrémentale des différents paramètres. Ainsi est-il possible de distinguer différents types de roman choral en fonction du degré de singularisation des voix, qui s’étend de la caractérisation la plus marquée (parlers régionaux, dialectes, argots, créoles, impuretés lexicales ou syntaxiques, ponctuations idiosyncrasiques) à l’absence de singularisation, qui dissout la spécificité des voix des personnages pour les fondre dans un fond atone.

Il pourrait aussi être intéressant de poser la question inverse de celle qui est habituellement posée à la fiction, non plus celle de l’adéquation d’une thématique à sa forme d’expression, mais celle des possibles narratifs que la structure chorale ouvre au récit. Ou, dit autrement, quel type de superstructure narrative l’infrastructure compositionnelle suscite-t-elle, favorise-t-elle, privilégie-t-elle ? Il serait ainsi possible de compléter l’analyse des formes possibles de la choralité par une typologie de ses contenus narratifs et par celle des formes privilégiées d’interrogation herméneutique, ontologique ou politique de la réalité et du monde.

Une étude de poétique historique, qui s’intéresserait au développement des différentes formes de roman choral dans le temps, et dans l’espace, serait ainsi bienvenue, ainsi qu’une enquête généalogique. À titre d’exemple, la relation de filiation du roman choral avec le roman du flux de conscience anglo-saxon ou le roman analytique français méritera d’être interrogée, ainsi que l’hypothèse selon laquelle le roman choral serait une évolution de ces derniers : le roman de conscience monophonique devenant, par multiplication des protagonistes, roman choral. Enfin, si l’on s’attache à distinguer les différentes composantes du genre (multiplication des protagonistes, composition mosaïque, délinéarisation de la narration, perspective plurielle, etc.), l’enquête pourra remonter plus avant dans le temps et reconnaître, non pas tant des précurseurs du genre, que des interrogations et des préoccupations proches dans d’autres types de fiction – la référence à La Comédie humaine est ainsi fréquente. La notion de choralité s’entendrait alors comme effet de lecture, et reconnaîtrait, dans un anachronisme motivé, des composantes chorales dans une œuvre qui ne l’est pas en première intention.

Le second moment de floraison du genre choral, dans les années 1990, devra aussi faire l’objet d’un examen approfondi. The Sweet Hereafter (Russel Banks) est publié en 1991 et Short Cuts (Robert Altmann) sort en salles en 1993. Depuis, le succès médiatique des œuvres chorales ne se dément pas : Imarat Ya’qubyan (L’Immeuble Yacoubian, 2002) d’Alaa El Aswany se vend à 100 000 exemplaires en Égypte ; en France, Lignes de faille (Nancy Huston) obtient le Prix Femina en 2006, et les ventes du roman atteignent 120 000 exemplaires. Pourtant, ce succès ne s’obtient-il pas au prix d’une simplification – d’un affadissement – de sa complexité formelle d’origine ? On pourra enfin s’interroger sur les convergences entre ces deux moments, d’apparition puis de refloraison, de la forme chorale, et ce qu’elles révèlent de leurs époques respectives.

Le propos de ce colloque sera avant tout théorique, et son ambition est de proposer une – ou plusieurs – définitions du roman choral, en intention comme en extension, ainsi qu’une typologie opératoire des différentes formes de récit choral. Selon le niveau d’analyse, les perspectives pourront relever d’une approche stylistique, narratologique, poétique, ou herméneutique. À ce titre, les études de cas sont bienvenues, mais à la condition qu’elle soient sous-tendues par une réflexion théorique sur la notion.

—

Les communications pourront se faire en français ou en anglais.

Les projets de communication (1500 mots), accompagnés d’une notice bio-bibliographique, sont à envoyer avant le 15 mars 2024 à aurelie.adler@u-picardie.fr, à marine.duval@u-picardie.fr et à christian.michel@u-picardie.fr.

—

English version

Poetics of the Choral Novel

While the adjective choral, borrowed to film criticism and subsequently to the literary field, is convenient and has seen some marketing and media success, the choral novel has not been the subject of a precise definition attempt. This present conference aims to explore the relevance, history, and metaphorology of this term, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive definition of chorality. In addition to those of the choir, whether musical or tragic, which deserve a specific examination, the metaphors invoked to describe the choral work must be the subject of careful study: “mosaic,” “kaleidoscope,” “puzzle”; “braided plot,” “crossway stories,” “network narratives,” etc. Also, the endeavor to delineate the uniqueness of chorality prompts inquiry into the position of the choral work—or the characteristics emphasized by the chosen adjective—within a broader array of concepts and generic categories linked to it: “dialogism,” “polyphony,” “plurivocality,” “heteroglossia”; “pluralist novel,” “book of voices,” “maximalist novel,” and so forth.

Also, it will retrace the genesis or crystallization of the genre. Aldous Huxley published in 1928 Point Counter Point. Menschen im Hotel. Kolportageroman mit Hintergründen (1929, Vicki Baum) was immediately adapted for the cinema (Grand Hotel, 1932, Edmund Goulding). As I Lay Dying (William Faulkner) appeared in 1930, shortly after Perrudja (1929, Hans Henny Jahnn), which was contemporary with The Sound and The Fury (1929), and two years later, Virginia Woolf published The Waves (1931). We should also mention Manhattan Transfer (1925, John Dos Passos) – usually considered a montage novel. And also Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929, Alfred Döblin), without forgetting the essential Ulysses (1918-1920/1922) by James Joyce.

Let us put forth, as a working hypothesis and initial approximation, that a choral work can be characterized by three distinct characteristics:

1. It features a mosaic of characters, giving voice to an orchestrated plurality of singular and subjective voices that alternate. In the choral novel, each narrator-character is defined by their words and/or thoughts, with idiosyncratic, idio- or sociolectal characteristics subject to specific investment.

2. It interweaves different narrative lines, composing a story of multiple and intertwined stories. This assumes both the independence of the stories and points of convergence, meeting, or crossing, which can be actualized in fiction or fall within interpretation. Delinearizing the narrative chronology, it arranges events in a tabular composition, promoting associations, locally or on a larger scale, through overlapping games, echoes, and resonances.

3. It offers a multi-perspectivist representation of reality, combining points of view, not to broaden, but to gradually identify, and ideally synoptically, a central event/character/object – often a blind spot. The choral novel is based on a tension between the restriction of the point of view and a symmetrically opposite attempt to compensate for this myopic constriction through a kaleidoscopic, faceted, or mosaic representation.

It is appropriate to study the relevance of this first definition while refining criteria to propose an operational typology of three different forms of choral work: first, stories where character-narrators, often witnesses, successively present their point of view on the same event/character/object (unity is action); second, stories where character-narrators know each other, cross paths, or meet without unified perspectives by a common event (unity is primarily a place: port, station, hotel, café, village, building, tower, even a cemetery, etc.); third, stories where narrator-characters have no common links/places.

We can further distinguish an optimistic and pessimistic version of chorality based on whether the multiplication of points of view enables the reconstitution of an absent or lost object. Alternatively, this attempt may fail, either due to a gap or an internal contradiction of points of view that cannot reach an agreement. Perhaps a third, intermediate category could be added, where the perceived event undergoes a shifted perception or a decentering of perspective, without affecting the coherence of the mosaic image.

The typology can be refined further through incremental variation of different parameters. It is possible to distinguish various types of choral novels based on the degree of singularization of voices, ranging from marked characterization (regional languages, dialects, slangs, creoles, lexical or syntactic impurities, idiosyncratic punctuations) to the absence of singularization, blending characters’ voices into an atonal background.

It might be interesting to pose the opposite question to the conventional inquiry into fiction. Instead of questioning the adequacy of a theme to its form of expression, we could explore the possible narratives that the choral structure opens for the story. In other words, what type of narrative superstructure does the compositional infrastructure elicit, foster, or privilege? This approach could complement the analysis of possible forms of chorality with a typology of narrative contents and the privileged forms of hermeneutic, ontological, or political interrogation of reality and the world.

A study of historical poetics focusing on the development of different forms of choral romance in time and space, along with a genealogical investigation, would be welcome. For example, questioning the filiation relationship of the choral novel with the Anglo-Saxon stream of consciousness novel or the French analytical novel, as well as considering whether the choral novel is an evolution of the latter. This entails exploring if the novel of monophonic conscience evolves into a choral novel through the multiplication of protagonists. By focusing on distinguishing the different components of the genre, the investigation can trace back in time to recognize similar questions and concerns in other types of fiction, such as the frequent reference to Balzac’s La Comédie humaine.

The second flowering of the choral genre in the 1990s requires in-depth examination. The Sweet Hereafter (Russel Banks) was published in 1991, and Short Cuts (Robert Altmann) was released in theaters in 1993. Subsequently, the media success of choral works continued, like Imarat Ya’qubyan (The Yacoubian Building, 2002) by Alaa El Aswany, which sold 100,000 copies in Egypt. In France, Lignes de faille (Nancy Huston) won the Prix Femina in 2006, with novel sales reaching 120,000 copies. However, it is worth questioning whether this success comes at the expense of a simplification or softening of its original formal complexity. One can also explore the convergences between these two moments—initial appearance and re-flowering—of the choral form and what they reveal about their respective eras.

The primary purpose of this conference is theoretical, aiming to propose one or more definitions of the choral novel, both in intention and extension. Moreover, it aims to establish an operational typology encompassing various forms of potential choral narrative. Depending on the level of analysis, perspectives may arise from a stylistic, narratological, poetic, or hermeneutic approach. While case studies are welcome, they should be underpinned by theoretical reflection on the notion.

Presentations can be in French or English. Communication projects (1500 words), along with a bio-bibliographic notice, must be submitted before March 15, 2024, to aurelie.adler@u-picardie.fr, marine.duval@u-picardie.fr, and christian.michel@u-picardie.fr.

__________________________

Bibliographie sélective

AZOULAY, Vincent, ISNARD, Paulin, « Athènes 403. Une histoire chorale », Flammarion, « Au fil de l’histoire », 2020.

ARONSON, Linda, The Six Sorts of Parallel Narrative, https://www.lindaaronson.com/six-types-of-parallel-narrative.html

BARNEY, Darin David, The Network Society, Cambridge, Polity, 2004.

BEAL, Wesley, LAVIN, Stacy, « Theorizing Connectivity : Modernism and the Network Narratives », Digital Humanities Quaterly, vol n° 5, 2011.

CASTELLS, Manuel, The Rise of the Network Society, Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

DEMANZE, Laurent, Un nouvel âge de l’enquête, Paris, Corti, 2019.

Dialogisme, polyphonie : approches linguistiques, Jacques Bres, Pierre Patrick Haillet, Sylvie Mellet, Henning Nølke et Laurence Rosier (dir.), De Boeck Supérieur, 2005. https://www.cairn.info/dialogisme-et-polyphonie-approches-linguistiques--9782801113646-page-339.htm

GENZ, Julia, « Il wullte bien, mais il ne puffte pas » – de la polyglossie à la polyphonie dans le roman Der sechste Himmel (Feier a Flam) de Roger Manderscheid, The Dynamics of Wordplay/ Enjeux du jeux de mots, Esme Winter-Froemel (dir.), De Gruyter, 2015.

FOSTER, Hal, The Return of the Real. The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century, Cambridge, 1996.

Livres de voix. Narrations pluralistes et démocratie, Alexandre Gefen, Frédérique Leichter-Flack (dir.), Colloques Fabula, https://www.fabula.org/colloques/sommaire8057.php

LECACHEUR, Maud, La littérature sur écoute : recueillir la parole d’autrui de Georges Perec à Olivia Rosenthal, thèse soutenue le 1er avril 2022 à l’ENS-Lyon, à paraître aux Presses universitaires de Saint-Etienne.

MESSAGE, Vincent, Romanciers pluralistes, Seuil, « Le Don des langues », 2013.

Polyphony and the Modern, Jonathan Fruoco (dir.), Routledge, 2021.

MALCUZYNSKI, M-Pierrette, « Polyphonic Theory and Contemporary Literary Practice », Studies in Twentieth Century Literature (Univ. of Nebraska), Mikhail Bakhtin, Clive Thomson (dir.), 1982.

Polyphonies : voix et valeurs du discours littéraire, Raphaël Baroni, Francis Langevin (dir.), Arborescences. Revue d’études françaises, n° 6, septembre 2016.

Plurivocalité et Polyphonies (Une voie vers la modernité ?), Rafaèle Audoubert (dir.), Garnier Classiques, 2022.

RABATEL, Alain, Homo narrans. Pour une analyse énonciative et interactionnelle du récit, Les points de vue et la logique de la narration (tome1), Dialogisme et polyphonie dans le récit (tome 2), Lambert-Lucas, 2008.

TOUYA, Aurore, La Polyphonie romanesque, Classiques Garnier, 2015.

VIART, Dominique, « Les littératures de terrain », Revue critique de fixxion française contemporaine, n°18, 2019, en ligne : https://journals-openedition-org.bnf.idm.oclc.org/fixxion/1275