La lune, entre sciences et imaginaires dans la première modernité Lunar Intersections : Early Modern Imaginings and Scientific Investigations

Lunar Intersections : Early Modern Imaginings and Scientific Investigations

La lune, entre sciences et imaginaires dans la première modernité

FRANÇAIS

Shakespeare en devenir n°21 (https://shakespeare.edel.univ-poitiers.fr/)

Call For Papers / Appels à contributions

Les deux publications astronomiques les plus importantes qui encadrèrent la vie de Shakespeare furent De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) de Copernic et Siderius Nuncius (1610) de Galilée. Si la théorie héliocentrique semblait être la découverte la plus choquante, la lune devint un sujet d’inquiétude, de spéculation et de recherche presque aussi important. L’ambassadeur anglais à Venise, Sir Henry Wotton, écrivit sur la publication de Galilée quelques jours après sa parution, notant que « le professeur de mathématiques à Padoue » avait, entre autres découvertes, montré « que la lune n’est pas sphérique, mais dotée de nombreuses protubérances et, ce qui est le plus étrange, illuminée par la lumière solaire réfléchie par le corps de la Terre ». Pour Wotton, cette découverte était donc aussi radicale que la révélation de Copernic : « il a d’abord renversé toute l'astronomie antérieure... puis toute l’astrologie ».

Mais avant même la publication de Galilée, les premiers auteurs modernes s’interrogeaient déjà sur sa nature. La lune permettait de mesurer le temps (« La lune est couchée. Je n’ai pas entendu l'horloge ») et régissait les marées ; elle représentait la folie et l’imagination (« le fou, l’amoureux et le poète »), la chasteté et l’érotisme (« La lune de Rome, chaste comme un glaçon ») et la catastrophe (« Hélas, notre lune terrestre est maintenant éclipsée »), parmi de nombreuses autres conceptions. Elle était personnifiée de multiples façons (« Dictynna... Un titre pour Phoebe, pour Luna, pour la lune »), peut-être plus que le soleil ; toujours féminine, la lune était à la fois inférieure au soleil, mais à bien des égards plus mystérieuse, plus présente dans les manifestations terrestres. Le Songe d'une nuit d'été de Shakespeare n’est que la plus évidente des nombreuses représentations dramatiques du pouvoir de la lune.

Nous invitons les auteurs à soumettre des articles sur les thèmes liés à la lune (représentations, invocations, spéculations) depuis l’imaginaire et les recherches scientifiques du début de la première modernité jusqu’aux applications contemporaines dans les domaines de la performance, de la théorie du genre, de la théorie queer et de l'écothéorie.

Sujets et questions suggérés :

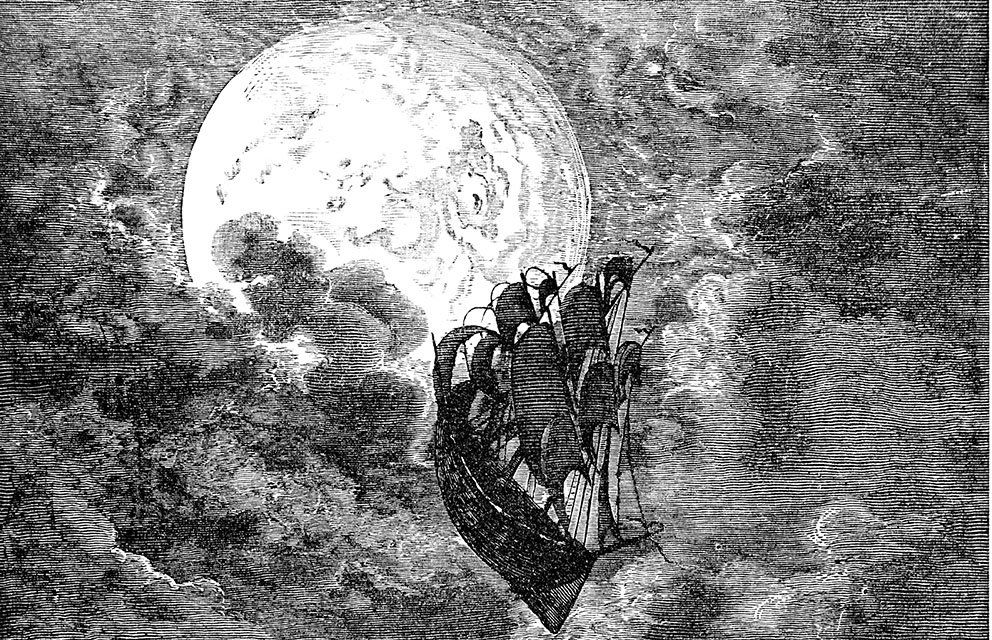

--les représentations visuelles de la lune

--Endymion et The Woman in the Moone de Shakespeare et Lyly

--la diffusion culturelle du Siderius Nuncius de Galilée

--les conséquences des découvertes de Galilée, par exemple dans News from the New World Discovered in the Moon (1620) de Ben Jonson et The Discovery of a World in the Moone (1638) de John Wilkins, jusqu'à l'exemple très différent de The Emperor of the Moon (1687) d'Aphra Behn

--la lune et le culte d'Elizabeth, tiré de « The Ocean to Cynthia » de Raleigh et des divertissements à Kenilworth et Elvetham, Hymnus in Cynthiam de George Chapman, l'iconologie des portraits royaux

--la longue association entre la lune et la folie

--la longue association de la lune avec les maladies dans le discours médical

--l'homme dans la lune : dérivation supposée de la Bible, liens avec Judas ou Caïn, et associations folkloriques

--les voyages vers la lune/la lune comme monde utopique, tirés de « A True Story » (publié en anglais en 1634) de Lucien, Somnium, seu Opus Posthumum de Astronomia Lunari (1634) de Kepler et The Man in the Moone: Or A Discourse of a Voyage thither (1638), jusqu'à L'Histoire comique des États et des Empires du Monde de la Lune (1659) de Cyrano de Bergerac.

ANGLAIS

The two most important astronomical publications bracketing Shakespeare’s life were Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) and Galileo’s Siderius Nuncius (1610). While the heliocentric theory seemed the most shocking discovery, the moon became nearly an equal locus for anxiety, speculation, and investigation. The English ambassador to Venice, Sir Henry Wotton, wrote about Galileo’s publication within days of its appearance, noting that ‘the Mathematical Professor at Padua’ had, among other discoveries, shown ‘that the moon is not spherical, but endued with many prominences, and, which is of all the strangest, illuminated with the solar light by reflection from the body of the earth’. For Wotton, then, it was as radical as Copernicus’s revelation: ‘he hath first overthrown all former astronomy . . . and next all astrology’. But even before Galileo’s publication, early modern writers puzzled over its nature. The moon enabled the measurement of time (‘The moon is down. I have not heard the clock’) and ruled the tides; it represented madness and the imagination (‘the lunatic, the lover, and the poet’), chastity and eroticism (‘The moon of Rome, chaste as the icicle’), and catastrophe (‘Alack, our terrene moon is now eclipsed’), among many conceptions. It was personified in multiple ways (‘Dictynna . . . A title to Phoebe, to Luna, to the moon’), perhaps more than the sun; always gendered female, the moon was both inferior to the sun but in many ways more mysterious, more present in earthly manifestations. Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is only the most obvious of many dramatic representations of the moon’s power.

We invite papers on representations, invocations, and speculations on lunar topics, from early modern imaginings and scientific investigations to contemporary deployments in performance, gender theory, queer theory and and eco-theory. Suggested topics and questions:

--visual representations of the moon

--Shakespeare and Lyly’s Endymion and The Woman in the Moone

--the cultural circulation of Galileo’s Siderius Nuncius

--the aftermath of Galileo’s discoveries, for example in Ben Jonson’s News from the New World Discovered in the Moon (1620) and John Wilkins’ The Discovery of a World in the Moone (1638), to the very different example of Aphra Behn’s The Emperor of the Moon (1687)

--the moon and the cult of Elizabeth, from Raleigh’s ‘The Ocean to Cynthia’ and the entertainments at Kenilworth and Elvetham, George Chapman’s Hymnus in Cynthiam’, the iconology of royal portraits

--the moon’s long association with madness

--the moon’s long association with diseases in medical discourse

--the Man in the Moon: the supposed derivation from the Bible, links to Judas or Cain, and folkloric associations

--voyages to the moon/the moon as utopian world, from Lucian’s ‘A True Story’ (published in English in 1634), Kepler’s Somnium, seu Opus Posthumum de Astronomia Lunari (1634), and Francis Godwin’s The Man in the Moone: Or A Discourse of a Voyage thither (1638), to Cyrano de Bergerac’s The Comical History of the States and Empires of the World of the Moon (1659).

DIRECTEURS DU NUMÉRO / CO-EDITORS

William C. Carroll (Boston University) & Pascale Drouet (Université de Poitiers)

William C. Carroll is Professor of English Emeritus at Boston University. Among his books: The Great Feast of Language, The Metamorphoses of Shakespearean Comedy (Princeton), Fat King, Lean Beggar (Cornell); and editions of Middleton, Women Beware Women (New Mermaids); Shakespeare, The Two Gentlemen of Verona (Arden), Love’s Labour’s Lost (New Cambridge). His most recent book is Adapting Macbeth: A Cultural History (Arden). He was President of the SAA in 2005-6. He co-chaired seminars at WSC (Berlin, 1986; Los Angeles, 1996) and at SAA and RSA in various venues. He has co-chaired the Shakespearean Studies Seminar at Harvard University since 1992.

Pascale Drouet is a Professor of early modern British literature at the University of Poitiers and the author of several monographs, the latest being Shakespeare and the Denial of Territory (MUP). She co-edited many collections of essays, including Dante et Shakespeare (Classiques Garnier) and, with W.C. Carroll, The Duchess of Malfi: Shakespeare’s Tragedy of Blood (Belin). She has published in Levinas Studies, Shakespeare Bulletin, Cahiers élisabéthain, Shakespeare, and lately contributed to The Changeling: The State of Play (Arden Shakespeare), Shakespeare on Screen: Romeo and Juliet (CUP).

DATE LIMITE D'ENVOI / DEALINE FOR PROPOSALS: December 2026

Les articles peuvent être en langue française ou en langue anglaise

Papers can be written either in English or in French

Please mind the stylesheet / Merci de respecter la feuille de style : https://shakespeare.edel.univ-poitiers.fr/index.php?id=1539

Les articles sont à envoyer à / Papers are to be sent to

pascale.drouet@univ-poitiers.fr & carrollwc@gmail.com

PUBLICATION : December 2027

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ELEMENTS

Bradley, Hester, “A Different Future on the Moon: Queer Genre and Time in A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, in Nicolas A. Tredell (ed), A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Amenia (NY), Salem Press, pp. 65-85.

Carroll, William C., “Goodly Frame, Spotty Globe: Earth and Moon in Renaissance Literature”, in Earth, Moon and Planets, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001, pp. 5-23.

Cox, Brian, “I Say It Is the Moon”, in Susannah Carson (ed), Living with Shakespeare: Essays by Writers, Actors, and Directors, New York, Vintage Books, 2013, pp. 199-219.

Cressy, David, “Early Modern Space Travel and the English Man in the Moon”, American Historical Review, October 2006, pp. 961-982.

Dauge-Roth, Katherine, “Femmes lunatiques: Woman and the Moon in Early Modern France”, Dalhousie French Studies, Summer 2005, Vol. 71, Summer 2005, pp. 3-29.

Davie, Mark, “Galileo and the Moon”, in Stefano Jossa and Giuliana Pieri (eds), Chivalry, Academy, and Cultural Dialogues: The Italian Contribution to European Culture, Cambridge, Northern Universities Press, 2016, pp. 153-163.

Fletcher, Angus, Time, Space, and Motion in the Age of Shakespeare, Cambridge (MA), Harvard University Press, 2007.

Hopkins, Lisa, “The Dark Side of the Moon: Semiramis and Titania”, in Annaliese Connolly and Lisa Hopkins, Goddesses and Queens: The Iconography of Elizabeth I, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2007, pp. 117-135.

Mallin, Eric Scott, “Moon Changes (Katherina)”, in Godless Shakespeare, London, The Arden Shakespeare, 2007.

Marchitello, Howard, “Telescopic Voyages: Galileo and the Invention of Lunar Cartography”, in Judy A. Hayden (ed), Travel Narratives, the New Sciences, and Literary Discourse, 1569-1750, Farnham, Ashgate, 2012.

Mattison, Andrew, “Shakespeare, Steevens, and the Fleeting Moon: Glossing and Reading in Antony and Cleopatra”, Shakespeare Quarterly, 2023 Summer, 74(2), pp. 90-113.

Pincombe, Michael, “The Woman in the Moon: Cursed Be Utopia”, in Ruth Lunney (ed), John Lyly, Surrey, Ashgate, 2011, pp. 315-330.

Tinguely, Frédéric, “Révolution copernicienne et voyage lunaire au dix-septième siècle (Kepler, Godwin, Cyrano), Colloquium Helveticum: Cahiers Suisses de Littérature Comparée, 2006, 37, pp. 231-246.

Trevor, Douglas, “Mapping the Celestial in Shakespeare’s Tempest and the Writings of John Donne”, in Judith H. Anderson and Jennifer C. Vaught (eds), Shakespeare and Donne: Generic Hybrids and the Cultural Imaginary, New York, Fordham University Press, 2013, pp. 111-129.

Valls-Russell, Janice, “New Directions: ‘The Moon Shines Bright’: Re-Viewing the Belmont Mythological Tapestry in Act 5 of The Merchant of Venice”, in Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin, The Merchant of Venice: A Critical Reader, London, Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare, 2020, pp. 125-144.

Valls-Russell, Janice, “‘So Pale Did Shine the Moon on Pyramus’: Biblical Resonances of an Ovidian Myth in Titus Andronicus”, Anagnorisis: Revista de Inversigacion Teatral, 2010 Dec., 2, pp. 57-82.

Vanhoutte, Jacqueline, “‘Age in Love’: Falstaff among the Minions of the Moon”, English Literary Renaissance, 2013 Winter, 43(1), pp. 86-127.

Zarins, Kim, “Caliban’s God: The Medieval and Renaissance Man in the Moon”, in Martha W. Driver and Sid Ray (eds), Shakespeare and the Middle Ages: Essays on the Performance and Adaptation of the Plays with Medieval Sources of Setting, Jefferson (NC), McFarland, 2009, pp. 245-262.