Gulliver’s Travels at 300. The Global Afterlives of a Bestseller in Print, Transmedial Adaptations, and Material Cultures (Seventh ILLUSTR4TIO International Symposium, London)

Plenary Lecture: Professor Daniel Cook (University of Dundee)

Artist’s Talk: Martin Rowson (in conversation with Brigitte Friant-Kessler)

Venue: St. Bride Library (London, U.K.)

Dates: 23–25 September 2026

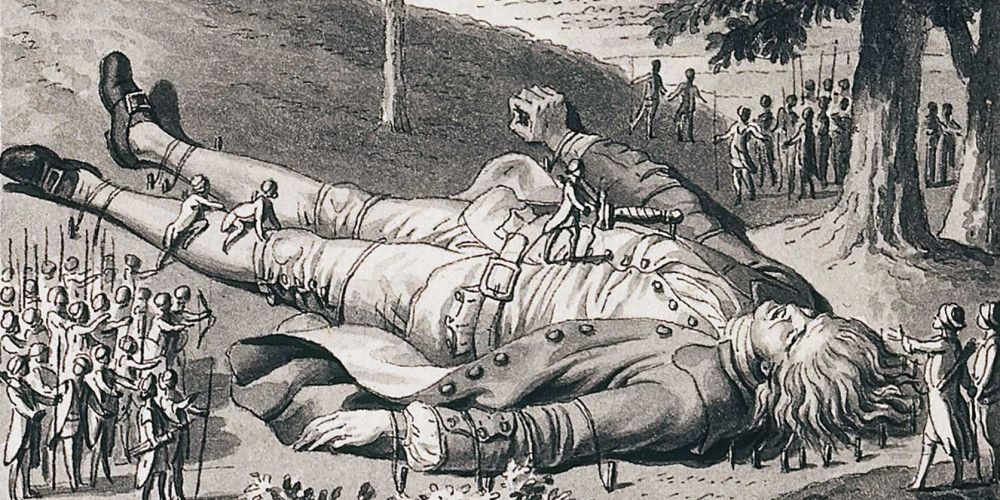

After Gulliver’s Travels was first published in 1726 and became, in the words of English dramatist John Gay, ‘universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery’, Jonathan Swift’s contemporaries provided mixed reviews of this prose satire, reflecting on its moral value, social landscape, political subtext, comic scenes, and general appeal as a fictional travelogue. The long list of famous figures who commented publicly or privately during Swift’s century on Captain Lemuel Gulliver’s memoirs includes Alexander Pope, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Samuel Richardson, Walter Scott, Abbé Desfontaines, Voltaire, Madame du Deffand, Johann Christoph Gottsched, and Christoph Martin Wieland. During its three-centuries-old existence, Gulliver’s Travels has been rewritten and reedited, imitated and parodied, abridged and expanded, visualised and adapted, commodified and collected…. ‘If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed’, wrote George Orwell in 1946, ‘I would certainly put Gulliver’s Travels among them’. And as Will Rossiter (@Satyrane), who is an X (previously Twitter) user and literary scholar, summed up its appeal using this platform on 2 June 2016, ‘the afterlife of Gulliver’s Travels is built into the text itself’. Less concerned with literary rhetoric and textual semantics, artists seized upon Gulliver’s Travels to engage creatively with a text punctuated with humorous scenes, set in apocryphal lands, and sewn with inventive plot twists, and in which the main character interacts with miniature creatures, giants, flying islands, and talking horses. In the process, they generated a multifaceted iconographic corpus that rivals those of eighteenth-century bestsellers such as Robinson Crusoe and Candide, which have benefited, however, from substantial critical attention.

As its tercentennial anniversary approaches, Gulliver’s Travels has established itself as a canonical text and global bestseller. It still resonates with readers, young and old alike, throughout the world, is successfully taught in university classrooms, inspires new visual and textual remediations and adaptations, and captures the consumer’s gaze from a wealth of material objects. Considered ‘a great classic’ written by ‘the preeminent prose satirist in the English language’, it is ranked number 3 on The Guardian’s 100 Best Novels (as ‘a satirical masterpiece that’s never been out of print’), 35 in Raymond Queneau’s Pour une bibliothèque idéale (listing books forming an ideal library), 55 on the BBC’s 100 Greatest British Novels (based on a poll distributed to book critics outside the U.K.), 62 on The Telegraph’s 100 Novels Everyone Should Read (inventorying ‘the best novels of all time’), as well as unnumbered in Die Zeit’s Bibliothek der 100 Bücher (a collection with pedagogical aims from the well-respected German newspaper) and Harold Bloom’s Western canon, listing works ‘of great aesthetic interest’. In the Greatest Books of All Time, an inventory generated by an algorithm from 130 lists compiling the best books including the aforementioned ones, Gulliver’s Travels is classified as number 36.

The Dean’s fictional travelogue has inspired a fascinating array of afterlives, ranging from the conventional (e.g. Sawney Gilpin’s 1760s oil paintings of Gulliver interacting with the Houyhnhnms and Thomas Stothard’s 1782 designs for The Novelist’s Magazine), to the loosely connected (Max Fleischer’s 1939 technicolour Gulliver’s Travels, recently restored for BluRay, and Gulliver’s Wife, Lauren Chater’s 2020 historical novel giving voice and agency to a midwife and herbalist whose presence in the source-text is minimal), to the transgressive (a fumetto: Milo Manara’s 1996 Gullivera; and American sailors from the Yokosuka Naval Base in Japan dressing up as Gulliver and parading in the Gulliver-Kannonzaki Festival), and to the playful (the giant Gulliver figure tied to the ground in Turia Gardens located in Valencia, Spain, with stairs, ramps, and ropes for children to climb up and down, as well as fast slides).

It is the enduring power and presence of Gulliver’s Travels in a diverse spectrum of fields, from scholarly editions to transmedial adaptations to popular culture events, that are of great interest to the conference organisers for this event. Papers that propose new, previously unpublished interpretations of the lively afterlives and global peregrinations of Gulliver’s Travels across time and space, or in various media and contexts, using interdisciplinary and cross-cultural approaches, are particularly welcomed.

Avenues for reflection include, but are not limited to, fresh perspectives on:

• the reception of Gulliver’s Travels in specific timeframes, geographic locations, and cultural contexts;

• Gulliver’s Travels in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century print (limited editions, serialised publications, chapbook adaptations, children’s books, ephemera, etc.);

• (illustrated) translations of Gulliver’s Travels in their editorial/linguistic/cultural contexts;

• Gulliver’s Travels and print culture (editorial paratexts, book collections, readers’ marginalia, extra-illustrated editions, etc.); or other graphic literature such as comics;

• images inspired by Gulliver’s Travels (paintings, frontispiece portraits, series of illustrations, standalone prints, graphic satire, maps, book covers, film posters, etc.) – focusing, for example, on visual commonplaces, iconographic paradigms, text-image relations, or Gulliver in the press;

• material Gulliveriana (board games, ceramic objects, playing cards, fans, keychains, bags, etc.) in relation to consumer culture and the Swift industry;

• the fun Gulliver (amusement parks, funfairs, cosplay, etc.);

• Gulliver’s Travels on stage (plays, musicals, operas, songs, sheet music) or on screen (film, TV, internet platforms, webzines, webcomics, video games, etc.)

• Gulliver’s Travels in the classroom: innovative pedagogical approaches to a world classic;

• decolonising Gulliver’s Travels and its links to the global British Empire;

• bringing Swift’s travelogue to life: curating exhibitions or events related to Gulliver’s Travels.Gulliver’s Travels at 300:

—

This international symposium celebrating the 300th anniversary of Gulliver’s Travels will be held under the auspices of the St. Bride Library in London, U.K. and in conjunction with a print workshop. In keeping with Illustr4tio’s aim to animate a dialogue between practitioners and critics, proposals are invited from illustrators, authors, printmakers, publishers, curators, collectors, and researchers. Papers can be presented in English or French. Proposals (500 words), accompanied by a bio-bibliographical note (100–150 words), should be sent to Gulliver’s Travels at 300 (gulliverat300@yahoo.com) by 15 March 2026. The publication of a selection of revised papers with previously unpublished material is envisaged.

We will be able to accommodate requests for an early decision to support funding applications (please indicate your deadline in the submission).

—

Organising Committee:

Nathalie Collé (Université de Lorraine)

Leigh G. Dillard (University of North Georgia)

Brigitte Friant-Kessler (Université de Valenciennes)

Christina Ionescu (Mount Allison University)

Illustr4tio is an international research network on illustration studies and practices. It aims at bringing together illustrators, authors, printmakers, publishers, curators, collectors, and researchers who have a common interest in illustration in all its forms, from the 16th century to the 21st century. (https://illustrationetwork.wordpress.com/)

—

References

Barchas, Janine. ‘Prefiguring Genre: Frontispiece Portraits from Gulliver’s Travels to Millenium Hall.' Studies in the Novel 30.2 (Summer 1998): 260-286.

Borovaia, Olga V. ‘Translation and Westernization: Gulliver’s Travels in Ladino’. Jewish Social Studies, New Series 7.2 (Winter 2001): 149-168.

Bracher, Frederick. ‘The Maps in Gulliver’s Travels’. Huntington Library Quarterly 8.1 (November 1944): 59-74.

Bullard, Paddy, and James McLaverty. Jonathan Swift and the Eighteenth-Century Book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Collé, Nathalie. ‘“[T]o Mix Colours for Painters” and Illustrate and Adapt Gulliver’s Travels Worldwide: Street Murals, Adaptability and Transmediality’. In Adaptation and Illustration, edited by Shannon Wells-Lassagne and Sophie Aymes, Palgrave Studies in Adaptation and Visual Culture (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2024), 47-68.

Cook, Daniel. Gulliver’s Afterlives: 300 Years of Transmedia Adaptation. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2026.

Colombo, Alice. ‘Rewriting Gulliver’s Travels under the Influence of J. J. Grandville’s Illustrations’. Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry 30.4 (October-December 2014): 401-415.

Cook, Daniel. ‘Vexed Diversions: Gulliver’s Travels, the Arts and Popular Entertainment.’ In The Edinburgh Companion to the Eighteenth-Century British Novel and the Arts, edited by Jakub Lipski and M.-C. Newbould (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2024), 228-243.

Cook, Daniel, and Nicholas Seager, eds. The Cambridge Companion to 'Gulliver’s Travels'. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Didicher, Nicole E. ‘Mapping the Distorted Worlds of Gulliver’s Travels’. Lumen: Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies 16 (1997): 179-196.

Duthie, Elizabeth. ‘Gulliver Art’. The Scriblerian 10.2 (1978): 127-131.

Edwards, A. W. F. ‘Is the Frontispiece of Gulliver’s Travels a Likeness of Newton?’. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 50.2 (July 1996): 191-194.

Friant-Kessler, Brigitte. ‘L’encre et la bile: Caricature politique et roman graphique satirique au prisme de Gulliver’s Travels Adapted and Updated de Martin Rowson’. In L’Image railleuse, ed. Laurent Baridon, Frédérique Desbuissons et Dominic Hardy (Paris: Publications de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, 2019), 315-344.

Gevirtz, Karen Bloom. Representing the Eighteenth Century in Film and Television, 2000-2015. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Goring, Paul. ‘Gulliver’s Travels on the Mid-Eighteenth-Century Stage; Or, What is an Adaptation?’ Forum for Modern Language Studies 51.2 (2015): 100–115.

Halsband, Robert. ‘Eighteenth-Century Illustrations of Gulliver’s Travels’. In Proceedings of The First Münster Symposium on Jonathan Swift, ed. Hermann J. Real and Heinz J. Vienken (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 1985), 83-112.

Hui, Haifeng. ‘The Changing Adaptation Strategies of Children’s Literature: Two Centuries of Children’s Editions of Gulliver’s Travels’. Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies 17.2 (Fall 2011): 245-262.

Léger, Benoit. ‘Nouvelles aventures de Gulliver à Blefuscu: traductions, retraductions et rééditions des Voyages de Gulliver sous la monarchie de Juillet’. Meta 49.3 (September 2004): 526-543.

Lenfest, David. ‘A Checklist of Illustrated Editions of Gulliver’s Travels, 1727-1914’. The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 62.1 (1968): 85-123.

Lenfest, David. ‘LeFebvre’s Illustrations of Gulliver’s Travels’. Bulletin of the New York Public Library 76 (1972):199-208.

McCreedy, Jonathan, Vesselin M. Budakov, and Alexandra K. Glavanakova (eds.). Swiftian Inspirations: The Legacy of Jonathan Swift from the Enlightenment to the Age of Post-Truth. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishers, 2020.

Real, Hermann Josef. The Reception of Jonathan Swift in Europe. London: Thoemmes Continuum, 2005.

Rivero, Albert J., ed. 'Gulliver’s Travels': Contexts, Criticism. New York: Norton, 2002.

Sena, John F. ‘Gulliver’s Travels and the Genre of the Illustrated Book’. In The Genres of 'Gulliver’s Travels', ed. Frederik N. Smith (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1990), 101-138.

Tadié, Alexis. ‘Traduire Gulliver’s Travels en images’. In Traduire et illustrer le roman au XVIIIe siècle, ed. Nathalie Ferrand (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2011), 149-168.

Taylor, David Francis. ‘Gillray’s Gulliver and the 1803 Invasion Scare’. In The Afterlives of Eighteenth-Century Fiction, ed. Daniel Cook and Nicolas Seager (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 212-232.

Wagner, Peter. Reading Iconotexts: From Swift to the French Revolution. London: Reaktion, 1995.

Welcher, Jeanne K. ‘Eighteenth-Century Views of Gulliver: Some Contrasts between Illustrations and Prints’. In Imagination on a Long Rein: English Literature Illustrated, ed. Joachim Möller (Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 1988), 82-93.

Welcher, Jeanne K. Gulliveriana VII: Visual Imitations of Gulliver’s Travels, 1726-1830. Delmar, N.Y.: Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints, 1999.

Welcher, Jeanne K. Gulliveriana VIII: An Annotated List of Gulliveriana, 1721-1800. Delmar, NY: Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints, 1988.

Welcher, Jeanne K. and Joseph Randi. ‘Gulliverian Drawings by Richard Wilson’. Eighteenth-Century Studies 18.2 (Winter 1984-1985): 170-185.

Womersley, David. Gulliver’s Travels. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.