« I would argue that literature exists only and always in its materializations,

and that these are the conditions of its meaning rather than merely the containers of it »

David Scott Kastan, Shakespeare and the Book

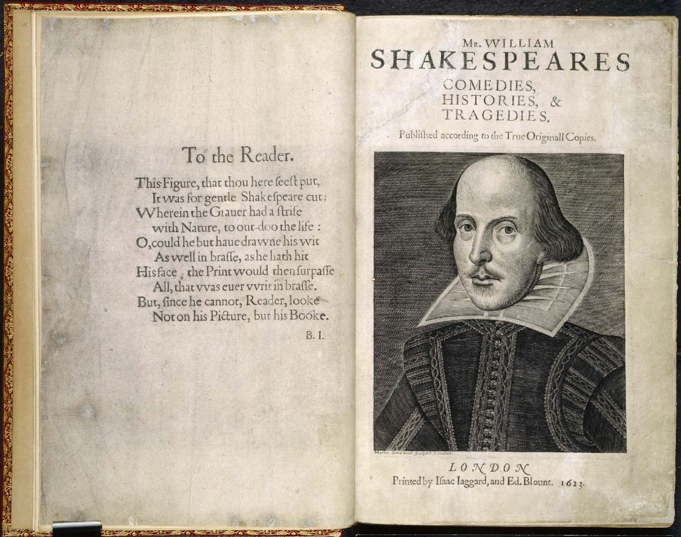

À l’occasion du quatrième centenaire de la parution du premier Folio de William Shakespeare, la Société Française Shakespeare propose pour le congrès de 2023 d’étudier non pas seulement l’un des plus célèbres (et des plus chers) livres du monde, mais de l’intégrer à une réflexion plus large autour des enjeux liés au format in-folio dans l’histoire du livre, de la littérature et des idées.

Plus qu’un gros livre, l’in-folio est un format qui porte en soi un sens particulier que n’ont pas, à ce degré, les autres formats plus petits. On notera évidemment que le Folio de 1623 n’est pas le premier. Deux illustres prédécesseurs parurent en 1616 : The Workes of Beniamin Jonson et The Workes of… Iames du roi Jacques VI d’Écosse / Ierd’Angleterre (voir Meskill). Contrairement à celui que Heminge et Condell publient, ils portent le titre d’« Œuvres », ce qui n’est pas anodin (voir Brooks). L’autre grand in-folio dans le domaine dramatique est celui des Comedies and Tragedies de Beaumont et Fletcher, paru en 1647, 15 ans après la réédition du Folio de Shakespeare. En Europe, on pensera également au De humani corporis fabrica de Vésale (1543).

Traditionnellement utilisé pour les livres d’histoire – The vnion of the two noble and illustre famelies of Lancastre and Yorke d’Edward Hall (1548), le Book of Martyrs (Acts and Monuments, 1563) de John Foxe, les Chroniques (1577) de Raphael Holinshed – le format in-folio, excepté l’in-plano, est le plus grand format d’impression des livres sans être entièrement normalisé.

Généralement, parce qu’il s’agit d’une publication luxueuse, l’in-folio se caractérise par la présence d’un paratexte très élaboré et très riche, qui fait intervenir un nombre conséquent d’auteurs / artistes et met en lumière le talent de l’imprimeur: titre, frontispice, sommaire / table des matières, épîtres dédicatoires plus ou moins nombreuses, poèmes d’hommage, index, illustrations et, bien sûr, attributions d’auteur. Ce paratexte contribue aussi à faire du livre un monument : celui de Shakespeare est présenté comme tel par les éditeurs et élevé à ce statut par les poèmes liminaires, celui de Foxe est « un juste tombeau » élevé aux mânes des martyrs, telle une châsse (voir le texte liminaire de Thomas Ridley).

En tant que tel, le format in-folio pose la question du statut de l’auteur ou des auteurs, comme cela apparaît nettement dans le cas de Shakespeare, mais aussi, dans un autre domaine, de George Chapman, qui publie ses traductions de l’Iliade (1609, 1611), de l’Odyssée (1614) et des Œuvres complètes d’Homère (1616, 1624) dans ce format. À ce titre, il pourrait être intéressant d’étudier les rapports entre l’in-folio et l’in-quarto, format de publication du théâtre à la Renaissance. En ce qu’il implique un investissement considérable (en argent, en temps, en main d’œuvre qualifiée), ce format prestigieux oblige aussi à considérer avec attention le rôle des imprimeurs et des libraires au sein d’un marché du livre en plein développement. La publication de ce type d’ouvrages est toujours une entreprise financière considérable : John Day faillit se ruiner pour le Book of Martyrs, à cause du coût du papier, et Heminge et Condell insistent lourdement auprès des lecteurs sur la nécessité d’acheter le livre avant toute chose (le nom de certains acheteurs d’in-folios est d’ailleurs documenté). Avant même la fabrication du Folio de 1623, il a fallu des tractations commerciales pour que les pièces détenues par les troupes puissent être rachetées afin d’être publiées.

Enfin, le terme même de « folio » incite également à envisager l’élément constitutif du livre qu’est la feuille et ses apparitions sur scène comme accessoires, sous forme de papier, de pages, de livres etc.

On invitera des communications sur les thèmes suivants :

– l’in-folio et la question générique

– l’histoire de l’in-folio

– l’in-folio et l’évolution et la signification du paratexte

– l’in-folio et le marché du livre

– l’in-folio et la question de l’auctorialité

– sociologie de l’in-folio

– l’in-folio dans les bibliothèques des XVIe et XVIIe siècles

– l’in-folio et la culture matérielle (encre, papier, techniques d’impression, etc)

– le « folio » comme objet théâtral

– la circulation des in-folios

– etc.

Merci de faire parvenir pour le 1er octobre 2022 votre proposition de communication (titre de la communication, mots-clés et résumé d’environ 300 mots) accompagnée d’une courte notice biobibliographique, à l’adresse suivante : [congres2023@societefrancaiseshakespeare.org]

Les réponses seront données le 15 novembre 2022. Les communications seront d’une durée de 20 minutes.

Comité scientifique:

Gilles Bertheau (Tours)

Claire M. L. Bourne (Penn State)

Jean-Jacques Chardin (Strasbourg)

Louise Fang (Sorbonne Paris Nord)

Claire Guéron (Dijon)

François Laroque (Sorbonne Nouvelle)

Sophie Lemercier-Goddard (ENS Lyon)

Jean-Christophe Mayer (Montpellier 3)

Anne-Marie Miller-Blaise (Sorbonne Nouvelle)

Eric Rasmussen (Nevada)

Cathy Shrank (Sheffield)

Christine Sukic (Reims)

Bibliographie:

Peter W. M. Blayney, The First Folio of Shakespeare, Washington DC, The Folger Library Publications, 1991.

Douglas A. Brooks, From Playhouse to Printing House: Drama and Authorship in Early Modern England, Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture 36, CUP, 2000.

Roger Chartier, La Main de l’auteur et l’esprit de l’imprimeur : XVIe XVIIIe siècles, Paris, Gallimard.

Charles Connell, They Gave Us Shakespeare: John Heminge and Henry Condell, London, Oriel Press, 1982.

Francis X. Connor, Literary Folios and Ideas of the Book in Early Modern England, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Line Cottegnies et Jean-Christophe Mayer, dir. « New perspectives on Shakespeare’s First Folio, Cahiers élisabéthains91,1 (2017).

Margreta de Grazia and Peter Stallybrass, « The Materiality of the Shakespearean Text, » Shakespeare Quarterly 44 (1993), 255-83.

Lukas Erne, Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist, CUP, 2003.

—, Shakespeare and the Book Trade, CUP, 2013.

Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography, New York & Oxford, OUP, 1972.

Anthony Grafton, The Culture of Correction in Renaissance Europe, London, 2011.

Walter Wilson Greg, The Shakespeare first folio : its bibliographical and textual history, Clarendon Press, 1955.

David Scott Kastan, Shakespeare and the Book, CUP, 2001.

Jeffrey Masten, Textual Intercourse: Collaboration, authorship, and sexualities in Renaissance Drama, Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture 14, Cambridge, CUP, 1997.

Lynn Sermin Meskill, “Ben Jonson’s Folio: A Revolution in Print?”, Études Épistémè 14 (2008).

Emma Smith, The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio, Oxford, Bodleian Library, 2015.

—, Portable Magic: a History of Books and their Readers, Allen Lane, 2022.

—

****English Version****

Annual Congress of the French Shakespeare Society

“Folio & Co: Shakespeare and the Theatrum Libri”

March 23-25th, 2023

Fondation Deutsch de la Meurthe, Cité Internationale, Paris 14e

« I would argue that literature exists only and always in its materializations,

and that these are the conditions of itsmeaning rather than merely the containers of it »

David Scott Kastan, Shakespeare and the Book

To celebrate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare First Folio’s publication, the French Shakespeare Society (Société Française Shakespeare) wishes to dedicate its 2023 conference to studying not only what is one of the most famous (and most expensive) books in the world, but to integrate it in a broader exploration of the role played by the folio format in the history of books, literature and ideas, as well as of its potential life on stage.

More than just a large book, the folio is a format that carries specific meaning, in a way that smaller formats do not. It will naturally be noted that the 1623 Folio is not the first of its kind. Two famous forerunners appeared in 1616, namely The Workes of Beniamin Jonson and The Workes of … Iames, by King James VI of Scotland/ I of England (see Meskill). Contrary to the one published by Heminge and Condell containing “Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories & Tragedies”, these are entitled “Works”, which is no minor point (see Brooks). The other large theatre-related Folio is the collected Comedies and Tragedies of Beaumont and Fletcher, which appeared in 1647, fifteen years after the reprint of Shakespeare’s Folio. As regards prominent European Folios, Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (1543) is worth mentioning.

Traditionally used for history books – such as Edward Hall’s The union of the two noble and illustre famelies of Landcastre and Yorke (1548), John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (Acts and Monuments, 1563) and Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles – the folio, though not entirely standardized, is the largest print format for books (except for the plano).

As a luxury format, the folio is characterized by an elaborate and rich paratext, which includes contributions by several authors/artists and showcases the printer’s skill – title, frontispiece, table of contents, dedications, tribute poems, indexes, illustrations, and of course, author attributions. The paratext also helps turn the book into a monument: Shakespeare’s Folio is presented as such by the editors and elevated to monumental status by its introductory poems, while Foxe’s is a ‘just tomb’ raised to the spirits of Protestant martyrs, in the manner of a shrine (see Thomas Ridley’s preface).

As such, the folio format raises the question of both its author or authors’ status and the authority of the text it contains, as is very clear in Shakespeare’s case, but also in the case of George Chapman, who (in another field) published his translations of the Iliad (1609, 1611), the Odyssey (1614) and the Complete Works of Homer (1616, 1624) in folio format. In this regard, it may be interesting to study the relationship between the folio and the quarto, the latter being the format of choice for theatrical printing in the Renaissance. Because it implied a considerable outlay (of funds, time and skilled manpower), the prestigious folio format also calls for careful consideration of the role of printers and stationers in a quickly expanding bookseller’s market. Publishing this type of book was always a high-risk financial venture: John Day nearly went bankrupt over the Book of Martyrs due to the cost of paper, while Heminge and Condell repeatedly urged readers to buy the book before judging it – indeed, some of these buyers’ names survive in various records. Even before the 1623 Folio was compiled, drawn-out financial negotiations had to take place before the playscripts owned by the playing companies could be purchased for publication.

Finally, the very term ‘folio’ may lead us to consider that constitutive part of the book, the leaf or sheet of paper, and its theatrical uses as stage property, whether in the form of a piece of paper, page, book, or other.

We welcome papers on the following topics:

· Shakespeare’s First Folio in the light of other folios

· The folio and the question of genre

· The history of the folio

· The evolution and meaning of the folio paratext

· The folio and the bookseller’s market

· The folio and the question of authorship

· The sociology of the folio

· The folio in 16th and 17th century libraries

· The folio and material culture (ink, paper, printing techniques, etc.)

· The folio as a theatrical object

· The circulation of folio volumes in Early Modern British, European, and Global networks

· Etc.

Please send your paper proposal (paper title, keywords and a 300-word abstract) by 1 October 2022, together with a short bio-bibliographical note, to the following address

[congres2023@societefrancaiseshakespeare.org]

Answers will be given on 15 November 2022. Papers will be 20 minutes long.

Scientific Committee:

Gilles Bertheau (Tours)

Claire M. L. Bourne (Penn State)

Jean-Jacques Chardin (Strasbourg)

Louise Fang (Sorbonne Paris Nord)

Claire Guéron (Dijon)

François Laroque (Sorbonne Nouvelle)

Sophie Lemercier-Goddard (ENS Lyon)

Jean-Christophe Mayer (Montpellier 3)

Anne-Marie Miller-Blaise (Sorbonne Nouvelle)

Eric Rasmussen (Nevada)

Cathy Shrank (Sheffield)

Christine Sukic (Reims)

Bibliography:

Peter W. M. Blayney, The First Folio of Shakespeare, Washington DC, The Folger Library Publications, 1991.

Douglas A. Brooks, From Playhouse to Printing House: Drama and Authorship in Early Modern England, Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture 36, CUP, 2000.

Roger Chartier, La Main de l’auteur et l’esprit de l’imprimeur : XVIe XVIIIe siècles, Paris, Gallimard.

Charles Connell, They Gave Us Shakespeare: John Heminge and Henry Condell, London, Oriel Press, 1982.

Francis X. Connor, Literary Folios and Ideas of the Book in Early Modern England, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Line Cottegnies and Jean-Christophe Mayer, eds. « New perspectives on Shakespeare’s First Folio, Cahiers élisabéthains91,1 (2017).

Margreta de Grazia and Peter Stallybrass, « The Materiality of the Shakespearean Text, » Shakespeare Quarterly 44 (1993), 255-83.

Lukas Erne, Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist, CUP, 2003.

—, Shakespeare and the Book Trade, CUP, 2013.

Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography, New York & Oxford, OUP, 1972.

Anthony Grafton, The Culture of Correction in Renaissance Europe, London, 2011.

Walter Wilson Greg, The Shakespeare first folio : its bibliographical and textual history, Clarendon Press, 1955.

David Scott Kastan, Shakespeare and the Book, CUP, 2001.

Jeffrey Masten, Textual Intercourse: Collaboration, authorship, and sexualities in Renaissance Drama, Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture 14, Cambridge, CUP, 1997.

Lynn Sermin Meskill, “Ben Jonson’s Folio: A Revolution in Print?”, Études Épistémè 14 (2008).

Emma Smith, The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio, Oxford, Bodleian Library, 2015.

—, Portable Magic: a History of Books and their Readers, Allen Lane, 2022.