Verbal and technical media in the multilingual poetry of Cia Rinne

Introduction

1The verbal, visual, digital, audio and spatial project Zaroum of the verbal and media artist Cia Rinne1 includes her conceptual poetry book zaroum (2001), its animated web-based work archives zaroum (2008), her second conceptual poetry book notes for soloists (2009), its sound work sounds for soloists (2012) as well as the related installations in art spaces around the globe2. Just as in her larger oeuvre, Rinne’s art is interwoven by a unique translingual literariness. The theoretical and methodological goal of this study is to define the major categories of translanguaging in general and to describe its text-internal and intermedial, but also its resemiotized, manifestations. The concept of translanguaging differs from that of multilinguality and code-switching in the sense, that in the works of Cia Rinne there is no clearly definable matrix language from the embedded language. In a translingual poetry, languages continuously switch their positions to such a high degree, that code-switching becomes the norm and not an exception.

2The practical goal of this study is to exemplify how translanguaging / translingual literariness / literary translingualism is thematically drafted and enacted as artistic form and aesthetic procedure in the works of Cia Rinne. First, a short description of the theoretical framework used is given, and its application in this study is highlighted. To further develop the theoretical framework of translanguaging as defined by Ofelia García, some elements of the formalist and structuralist as well as contemporary poetics will be used (here referring only to Roman Jakobson and some contemporary scholarship, as of Kilchmann3 and Benthien et al4.). By investigating some particularly innovative translingual artistic techniques of Cia Rinne, this paper makes a general contribution to the methodology of literary translanguaging. The last point of the study addresses the philosophical questions behind the work and their arc in the history of the humanities.

Translanguaging

3Authors writing in different languages as well as texts using several languages have always been present in literary writing. However, the use of different linguistic codes in one piece of literature has often been strongly censored in the process of writing as well as in the process of transferring manuscripts to print. Since it is now once again garnering stronger publicity, translanguaging merits a more thorough consideration by literary scholars. This study focuses on textual enactments of literary translingualism, namely of translanguaging patterns and their poetic function.

4Distancing herself from monolingual and monoglossic language ideologies, the sociolinguist Ofelia García defines translanguaging as the act performed by multilinguals—or bilinguals, as she calls them below—

of accessing different linguistic features or various modes of what are described as autonomous languages, in order to maximize communicational potential. It is an approach to bilingualism that is centered, not on [the concept of separated] languages as has often been the case, but on the practices of bilinguals that are readily observable in order to make sense of their multilingual worlds5.

5As García suggests for evaluating everyday translingualism, this study turns its attention towards the performative aspect of literary translingualism in order to “recognize the value of heteroglossic discourse and multiple voices6”. It is this decentered, dehierarchized heterolinguality that this study takes as its major approach in analysing literary translingualism.

6Cia Rinne was born in 1973 to Finland-Swedish and Finnish parents in Gothenburg, Sweden, but at the age of four months she moved to Germany with her family and grew up in the wider metropolitan area of Frankfurt am Main. Her family history, combined with the effects of the multilingual neighbourhood where she grew up as well as her studies and fieldwork in several countries, have definitely been a source of great inspiration for her art. Her books have been published in Sweden, Denmark, Germany, France, Switzerland and Canada, starting with the above-mentioned books of the Zaroum project, or the most recent l’usage du mot (2017), sentences (2019), and I am very miserable about sentences (2019).

Image no. 1, The 2017 Kookbook publication unites the new poems of l’usage du mot (2017) along the two previous volumes of zaroum (2001) and Notes for soloists (2009)

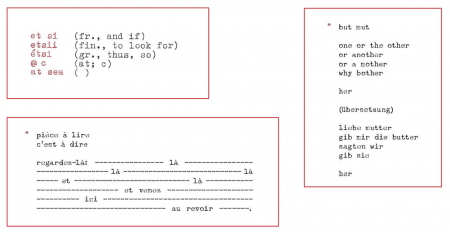

7Rinne’s works contain typewritten, multilingual texts shaped into printed, digital, audio and spatial poetic forms. Verbal idioms, clichés and philosophical reflections are nearly always structured along patterns of word and form play. The linguistic elements are accompanied, and sometimes intertwined, with diagrams: boxes, lines, circles, flow charts, drawings, collages and multiple-choice questions. These works undoubtedly stand as great pieces of poetic work, with their combination of direct and indirect references to the artists of the transcultural Fluxus and Dada movements as well as some prominent philosophers of language, such as Tomas Schmit, Emmet Williams, Arthur Köpcke, Lev Rubinstein, Marcel Duchamp, Ilya Kabakov, Steve Reich, John Cage, Yoko Ono, Gertrude Stein, Karlheinz Stockhausen, René Magritte, Nina Hagen or Ludwig Wittgenstein. Rinne’s conceptual works are very coherent with her digital works as well as her space, sound installations and live performances, on which the study reflects in its closing part. Her performances, exhibitions and sound installations have been shown internationally in galleries and museums such as Den Frie and Overgaden in Copenhagen, Signal in Malmö, the KUMU Art Museum in Tallinn, Bielefelder Kunstverein, Weserburg Bremen, the CNEAI in France, the ISCP in New York, and at INCA Seattle. Her recent sound work leçon du mot [le son du mot] (with Sebastian Eskildsen) was premiered in the Glyptothek of Copenhagen in 2018. For an opera by Henrik Strindberg and Sofia Jernberg premiered at the Royal Opera in Copenhagen in November 2019, Rinne wrote the libretto (Trial&Eros). She is also the laureate of the Prix littéraire Bernard Heidsieck – Centre Pompidou 2019.

8Rinne's visual poetry has attracted growing international recognition both in terms of its textuality (regarding her wordplay), as well as its intertextuality (within visual art and music), and in terms of its contextuality (the socio-political message of her art). Some analyses focus on her use of abundant stylistic devices such as anagram, permutation, mesostic, collage, sound echo, homonym and paragram, or to the sound implications of the works. Other studies consider the interplay of the visual and aural with the topologico-conceptual. The conceptuality of Rinne's visual poetry has been compared to the 1960s Swedish typewriter experiments (to Bengt Emil Johnson, Mats G. Bengtsson, Kurt Sanmark), to the so-called “dirty” concretism (to Bob Cobbing, Steve McCaffery), or to French spatialisme (to Ilse and Pierre Garnier, Henri Chopin). Contextualizing her unique ways of generating new and radical modes of negotiating language and meaning, some critics have discussed Rinne's art in reference to the Deleuzian and Guattarian concepts of rhizomatic structure and deterritorialization, and as a possible political engagement with the world according to Karen Barad’s idea of “entangled agencies” and Rasmus Fleischer’s concept of “the postdigital”. Translanguaging, however, has never been considered the key device for Rinne's poetic architecture. By contrast, this forms the main focus of the present analysis, which looks at how translanguaging is enacted as topic and how it is formally as well as stylistically modelled in the art of Cia Rinne. The thesis of this paper draws our attention on one hand to the fact that the different techniques of translanguaging make the reader conscious of how signs acquire the power of the symbolic (i.e., generate the semantic level) and shape our understanding not only of languages but also of art. On the other hand, different modes of resemiotization of translingual poetry point out creative patterns common to several arts.

From theory of translation to the theory of translanguaging

9In his seminal paper on the theory of the poetic, Poetry of Grammar and Grammar of Poetry, Roman Jakobson makes a distinction between the paradigmatic and syntagmatic dimensions of a semiotic system. The former describes the process of selection, the latter that of contamination of linguistic items or signs. According to Jakobson, “[t]he poetic function projects the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection into the axis of combination7”. In poetry, Jakobson rightly emphasizes that the equivalent forms are not lost in the chain of discourse, and the principles of selection are easier to point out. The following sections address the ways in which translanguaging, as a special aesthetic device, contributes to the poeticality of multilingual literary and artistic works. In our examples the axis of selection manifests itself through the accessibility of various verbal, audio and visual codes—through the higher number of signifiers for the equally elusive signified. Furthermore, this study demonstrates through looking at multilingual artistic outputs, what Emilee Moore and Jessica Bradley underline in their 2020 study on text and sound transformation, that artistic intermediality (or as they name it, resemiotization) is indeed another valuable lens for conceptualising translanguaging.

10Much as Roman Jakobson makes a very important distinction between three types of translation in his other seminal paper, On Linguistic Aspects of Translation (1959/2000), translanguaging can be broken down along similar lines, into intralingual, interlingual and intersemiotic translanguaging. Jakobson's theory works with well-delimited source and target text concepts, with individual texts that are ontologically relatable to each other. With translanguaging, however, the multiplicity and continuous interplay of different codes is the norm, and the following sections will discuss individually the different categories of translanguaging. While the driving force of Russian Formalism was “the desire to identify literature—and art in general—as a way of revitalizing human perception8”, the driving force behind translanguaging is to revitalize human perception in general and on art and languaging in particular through the reservoir of multilingualism. Both modalities point out that in contemporary media art “the perspective of literariness dissolves binaries between materiality and meaning, the phenomenological domain and the realm of interpretation9”.

Thematic translanguaging: interwoven languages and images

11In Rinne’s poetry, thematical translanguaging is addressed at only a few points. These include the dictionary-like entry in “et si” indicating the origin of the homophonic words, the addressed intersemiotic aspect of language, that of its orality and written medium in “pièce à lire / c’est à dire”, and through an indication of the translation process, “(übersetzung)”, between texts in our example on the right of the following figure:

Image no. 2, Examples for thematically addressed translanguaging

12Approaching the text through its multilingual dimension, we immediately note that the preponderant English, French and German meet some Italian, Spanish, Russian, Swedish, Finnish, Greek and maybe Romanian. Pages in just one language are rather rare, while pages with two or three languages are the rule, and pages with more than three languages are not infrequent. In this glossolalia, as Lundberg formulates it, “Languages meet and collide, they slide into each other, and you are not sure which language you read10”. Languages and images interwoven by the author collide strongly with the linguistic and artistic competences of the reader, and that is precisely where these texts are in constant transmutation. For example, although Rinne quite likely did not mean to include any Hungarian words, Hungarian readers will nevertheless detect some. Or, equally likely, Rinne did not have Malevich’s black square in mind, yet it will be impossible for some readers to ignore it when seeing her squares on the page.

13 In order to lend full consideration to the formal and stylistic aspects of translanguaging, the following sections address the ways in which translanguaging, as a special aesthetic device, contributes to the poeticality of multilingual literary works and beyond. Here the axis of selection manifests itself through the accessibility of various linguistic codes—through the higher number of signifiers for the equally elusive signified. By adding the dimension of translanguaging, more precisely how multilingual elements deconstruct and recode our lingual and poetic awareness, Anna Katharina Schaffner’s description of the historical avant-garde poetry could also be applied to literary translingualism of Cia Rinne’s art as well:

The taking apart of linguistic units from text to word, the discovery of the visual and acoustic dimension of the linguistic sign, the instrumentation of typography, the reduction of the word material and the conceptual use of space by means of non-linear arrangement of letters on the page are vital innovations of the movements of the historical avant-garde. Of particular interest… is their distinct method of operating with language: the foregrounding and scrutiny of the linguistic material, the poetic act of cutting open and laying bare structures and properties of language at different levels of organization—be it at the level of text, sentence, word or letter, at the level of semantic compatibility, syntax, lexicology or phonetics11.

Intralingual translanguaging

14The category of intralingual translanguaging draws our attention to the combination of different diachronic and synchronic segments of a language which in our case is embedded in other language(s), for instance, when vernacular and literary, slang and institutional styles of one and the same language are combined and presented in other language environments. This kind of polyphony—“multi-generic, multi-styled, mercilessly critical, soberly mocking, reflecting in all its fullness the heteroglossia and multiple voices of a given culture, people and epoch” as Bakhtin12 described it—is to different degrees inherent in literary works, and in different ways constituted through the processes of reception. For this category there are excellent examples from German-Turkish authors like Emine Özdamar, or authors such as Zé Do Rock using Kanakisch, Giana Barschi using Spanglish in their books, as well as Hamadi Khemiri who uses Rinkeby Swedish.

15As underlined above, the category of intralingual translanguaging draws our attention to the combination of different diachronic and synchronic segments of a language embedded in other languages, for example, when vernacular and literary, slang and institutional styles of a language are combined and presented in other language environments. In Rinne's books we can find two different kinds of intralingual translanguaging: grammatical permutation and heteroglossing with elements of various sociolects and dialects. Although we speak here of monolingual sound and word patterning, these elements are likewise considered to be part of translanguaging, since they play a special role in the multilingual texture of the book.

Grammatical permutation

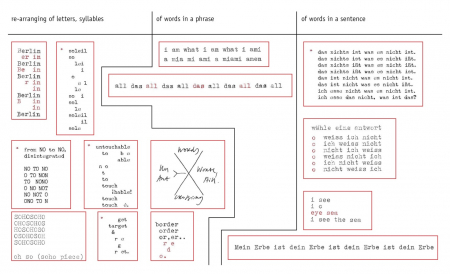

16The re-arranging of letters, syllables in a word, or of words in a sentence is a very favoured device in Rinne's poetry, which it could called code-breaking instead of code-switching. Rinne breaks down words, phrases and sentences into constitutive parts and then rearranges them in a way that allows the structure and constitution of languaging to stand out. Examples of the permutation of word elements, that of lexical, morphological and phonetic/phonologic units with multilingual implications are included in the first column of the figure below (like the “SOHOSOHO… oh so piece” or the poem starting with “Berlin / er in / Berlin” or playing with “Un- / Ant- / Worte, still” in the handwritten excerpt. Examples demonstrating the permutation of elements of a phrase (like “i am what i am what i ami / a mia mi ami...” or “all das all das all…”) and the permutation within a sentence (like “das nichts ist was es nicht ist …” or in “weiss ich nicht / ich weiss nicht…”) are included in the second and third column.

Image no. 4, Grammatical permutations

17These permutations and mutations of grammatical elements are accentuating the modes of selection of the language. The syntactic level of a literary language would accept just a few of these examples as grammatical and therefore usable. However, when we focus on the constitutive elements of linguistic units, our everyday language use is de-automatized or regressed to the learning phase of early childhood. This insight into the laboratory of the language’s form and meaning production is interwoven with multilingual processes. Due to the fact that several languages are used in the book, intralingual grammatical permutations will be approached multilingually. And indeed, the reader will hesitate at the first sight of an “in”, wondering whether it is from German, English or Swedish, just as the “er” might be from German, Swedish or Danish. Such moments demonstrate that multilinguality is inherent in the lingual, just as the lingual is inherent in the multilingual.

Heteroglossing

18Still as part of intralingual translanguaging technique in Cia Rinne’s poetry, the phenomenon of heteroglossing with elements of a language’s dialects and sociolects is less often manifested; however, it is not unattested. Both examples available are from her second book, and these include the Berliner pronunciation of the literary form: “keine” as “keene”, and the poem echoing the German Kanakish: “... du sollst nicht lachen / liebe gott böse ... / du sollst nicht schöne augen machen / fremde leute / liebe gott wirklich böse”, (that translates in English as “you shall not laugh / dear god angry / you shall not throw nice eyes / foreign people / dear god really angry”).

19While the other language examples in the book never evoke a specific socio- or dialect, the German heteroglossing anchors the text in a multilingual, multicultural context to present-day Germany.

Interlingual translanguaging

20Known also as heterolingual writing, interlingual translanguaging operates with diverse linguistic codes. Among the most important effects these works have on the readers is the de-automatization of the semantic routines used in monolingual communication. By gaining insight into how meaning is generated in particular languages, the reader is prompted to reflect on human cognitive processes in general. Interlingual translanguaging has structural and functional similarities with poetic language, drawing the paradigmatic dimension to the foreground13, and it will definitely gain more recognition in the “post-monolingual” cultural criticism to come14.

21 While proceeding to the next category, interlingual translanguaging shows anchoring the text in the tradition of concrete or visual poetry/art. Known also as heterolingual writing, interlingual translanguaging operates with diverse linguistic codes. Among the most important effects these works have on the readers is the de-automatization of the semantic routines used in monolingual communication. By gaining insight into how meaning is generated in particular languages, the reader is prompted to reflect on human cognitive processes in general. Interlingual translanguaging has structural and functional similarities with poetic language, drawing the paradigmatic dimension to the foreground, and it will definitely gain more recognition still in the “post-monolingual” cultural criticism to come.

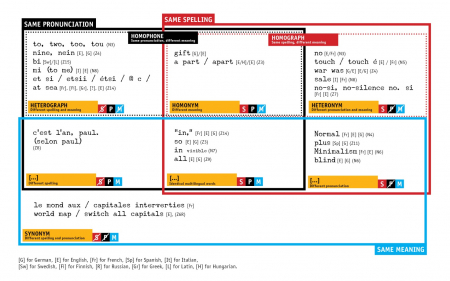

22 The frequency of wordplay across different languages in Rinne’s poetry activates the multilingual paradigmatic axis. Through it we gain special insight into the interdependency of pronunciation and spelling (form) and meaning (content), which is achieved through several patterns of homophoning, homographing and synonyming. Their intersecting examples are marked with black (for homophoning), red (for homographing) and blue (for synonyming) squares in the following figure. The disambiguation of these elements might be a goal for linguistics, but definitely not for Rinne’s poetics. To refer to the possible language provenance of the linguistic items being analyzed, initial letters are used to refer to individual languages, as [G] for German, [E] for English, [Fr] for French, [Sp] for Spanish, [It] for Italian, [Sw] for Swedish, [Fi] for Finnish, [R] for Russian, [Gr] for Greek, [L] for Latin, or [H] for Hungarian.

Homophoning

23Homophones are words—as well as units longer or shorter than words—which are pronounced the same but have different meanings (they can be spelled the same too, i.e., homographs, or not). The majority of the homophones activated in Rinne’s texts belong to the category of heterographs—multilingual units with same pronunciation but a different spelling and a different meaning. This category includes examples as the English “to, two, too”, along with the French “tou”; or the English “nine” together with the German “nein”.

24 Examples from the other subcategory, called homonyms, occur much less frequently. Rinne’s homonyms are built of multilingual linguistic units with the same pronunciation as well as the same spelling but having different meanings. For the list of homonyms the figure includes examples of “a part / apart” meaning ‘the shore’ in [H] or “a portion” in [E] along with the English or German word “apart” or the German and English word “gift” meaning ‘poison’ or ‘present’, respectively.

Homographing

25From a large number of Rinne’s homographs—multilingual units, which are spelled the same but carry a different meaning, and where the pronunciation may or may not be the same—examples for the multilingual heteronyms are placed into a red dotted square. This includes words with the same written form but different meaning and different pronunciations, like for example “No” as negation and numero sign in [E] or [Fr]; or “war was” as ‘the opposite of peace’, past tense expression in English, or as ‘was there anything’ in German, or “sale” as [I] and [Fr] words meaning ‘salt’ or ‘dirty’, respectively.

Synonyming

26Examples of synonymic play with multilingual words with the same spelling, same meaning, but different pronunciation, are placed into the blue square, as the lines of “le monde aux / capitales interverties // world map / switch all capitals”, which contain a French text followed by its English translation. The few mainly identical multilingual words include “in”, “so”, “all” found in a dozen poems. Moreover, the only multilingual polysemic example detectable in the book is “gift”.

Image no. 6, Interlingual translanguaging with overlapping spelling, pronunciation and meaning

27Rinne’s texts challenge the traditional sender-receiver model of language, which assumes a unidirectional decoding process. Her multilingual play with spelling, pronunciation and meaning multiplies the degree of implicit information relevant to the text, as well as the limits that help the reader to mobilize from the context. Moreover, it aggravates the demand on the reader to cooperate and experiment. Activation comes to the reader from many angles. As Beetz points out, this occurs simultaneously on four levels: the motoric, the perceptual and the emotional and cognitive15.

Intersemiotic translanguaging

28In intersemiotic translanguaging, multiple verbal signs accompany nonverbal ones such as music or images. In her recent paper on the poetics of foreign language, Kilchmann briefly addresses the structural similarities between multilingual and experimental poetry16. Within multilingual visual poetry both these traditions meet. Indeed, in intersemiotic translanguaging, it is not only the paradigmatic aspect of the interlingual that plays a pivotal role, but also the conjunction of multilingual and multimedial aspects. 21st century visual poetry is only the continuation of a centuries-long tradition of artistic experimentation: the concrete poets of the 1950s–60s have their direct antecedents in historically recent avant-garde movements (symbolist, dadaist, futurist, surrealist) or early modernists, but such experimentation dates back as far as shape poems17 or even further to Wordalgebra or even to the Greek Magical Papyri (2nd century BCE to the 5th century AD). Although most of the visual poets and artists of the past century were multilingual, the frequency of translanguaging in visual poetry is not proportionate. This fact underlines the unique character of the poetry we are going to analyze below.

29The third type of translanguaging considers the role of multilinguality in the interplay of linguistic and visual signs. The interplay between text and image can itself be documented quite early in the history of poetry (e.g., the ideogrammatic poems of Simmias of Rhodes and Theocritus of Syracuse, around 300 AD). Besides using many devices from 20th century visual poetry, Rinne’s poetry becomes truly unique with the consequent implementation of translanguaging.

30Rinne’s works often combine traditional verse structure (a few words below each other and lines left-justified) with other visual effects. Mesostic, v-shape, application, and multiple-choice forms underline the vertical in the horizontal of the text.

31In the multilingual mesostic poem from Zaroum, the horizontal lines of verse are intersected in the middle by a vertical phrase that reads “Siah Zaroum”. The poem is written in English and German, and beside as a homophone for her name Cia, it is impossible not to think of the associations of mes/siah, the crucification of the text, of multilinguality or of both in one: that of multilingual poetry.

Image no. 7, The mesostic poem “Siah Zaroum”

Translanguaging of the alphabetical with the numerical and the musical

32When considering translanguaging between the multilingual and other, so-called “countable”, semiotic systems, one notices the intertwining of the alphabetical with the numerical and, in a few cases, with the musical notation system. The resulting intermedial configurations remind us of the dream keys of Magritte, as well as of the aleatoric music of Cage and the serial music of Nono—just to mention immediate connotations of the text. The two examples listed below from Z2, Z15 (from Zaroum) and N5, N8 (from Notes for soloists) remind us of rebus puzzles, which use existing symbols such as pictograms, numbers, etc. for their sound effect.

Image no. 8, Translanguaging with the numerical and the musical

33These examples underline the role of denotation systems, without which the intermedium of concrete poetry would also not exist. They also underline the wide variety of visual codes that culture provides us in order to materialize ideas, sounds and thoughts. However, none of these systems are overused by Rinne. Their minimalist use keeps us focused on how these codes transition from the real into the symbolic18, from the semiotic to the symbolic19.

Interplay of multilingual and geometric

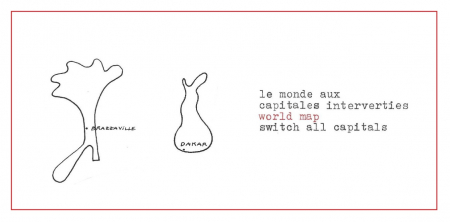

34The type of intermedial translanguaging takes into consideration the role of the multilingual in the interplay of geometric and free forms: boxes, outlines of countries, sketches, collages, etc. This multisemiotic play provokes conventional reading patterns, urging readers to find and experience the work in a way that is uniquely their own. In the following example from Z6, Rinne overlays the shapes of Italy and Finland with the capitals of Congo and Senegal.

Image no. 9, Interplay of multilingual and multimedial

35This interplay of multilingual and visual codes adds to the passage’s semantic density as well as its intensity. It spatializes the multilingual by giving the translingual an original, playful figuration. Rinne’s translanguaging transcends the semanticity of language and of languages. Minimal verbal and visual units start long contemplations on their journey. Many literary critics consider that multilingual literary works “focus on the transition between individual languages and use it systematically to produce effects of alienation20”. However, in the case of Rinne as well as of readers with multilingual everyday lives, it is not the alienation (Verfremdung) but rather the naturalness of translanguaging that juts out in the foreground. The effect for the author as well as certain readers is the feeling of liberation. Here is an underlining quote by Rinne from the recent book I'll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women, edited by Caroline Bergvall:

What is interesting about conceptual as well as translingual writing is its ability to disrespect the grammar of habitual communication, to operate beyond logics, and to ignore the strict definition of language as well as the constraints and requirements that other, ‘more serious’ writing genres are confined to. The different methods conceptual writers use can oblige certain rules, but conceptual writing in itself will with difficulty be defined according to such. It is not limited by the constraints of one single genre, but operates freely on the borders of many disciplines, and some pieces of conceptual writing can indeed be closer to pieces of visual, sound, or performing arts. There is something very liberating to language operating beyond its commonly accepted functions; you could call it linguistic anarchy, and although this aspect is not a goal in itself, it is certainly essential to conceptual writing.

Some pieces of conceptual writing have a certain esprit that goes beyond humour, and which I think is quite specific for such texts. In a way, conceptual texts operate on many different levels simultaneously. Besides their awareness on form and content, there is often a metatextual aspect to them. To a certain extent, language transforms into something else and reaches beyond its function as a mere means of communication21.

Resemiotization of translingual poetry in Cia Rinne’s Zaroum project

36With her digital, sound and installation works, Rinne radicalizes our exposure to the materiality of sign. By taking her multilingual concrete poems and turning them into digital, the boundaries between art forms get blurred and previous motives from her poetry books are retaken and reactualized in a new form. This transmedial method enriches our understanding of translanguaging by arousing the visual of the literal, the rhythmic, melodious, playful use of the language, as well as the homophoning and transversal aesthetics of the translingual. Moreover, it manifests how different arts can incorporate the same motive, in our case how translanguaging slips out from a hypermedial poetry into another kind of hypermedial performance.

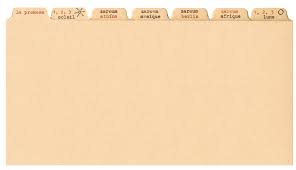

37Rinne’s minimalist animated poetry experiment, archives zaroum, builds upon seven digital index cards each of them hosting longer poetic trails one can access by clicking on its elements.

Image no. 10, archives zaroum, content list

38By transforming “script as typogram” of the book in “script as typocinetogram22” the materiality of knowledge, of art becomes dominantly exhibited. Thinking back to the earliest clay tokens, the ancient Sumero-Accadian clay tablets, Hellenistic parchment, the Rosetta or the Orkhon stone inscriptions up to the printed paper books and our multimedia texts, the clay-colored digital index cards of archives zaroum reflect on all kind of writing media used in human history. Moreover, on these screen cards minimalist and playful philosophical questions on human existence are manifested. Images contain red and black letters, drawings, sentences, wordplays, rhymes. The reader has a different kind of freedom in getting ahead on the screen than on pages of a book but she or he remains still possessing the so called “dural” of the printed.

39When the multilingual concrete poetry is resemiotized as sound poetry within Rinne’s sounds for soloists, the “dural” of translanguaging, namely the visual of the printed or digital text, meets a different dimension, that of the “temporal”, of the spoken sound. By the transformative gesture of the visual into auditive memory, a further radical semiotization of the translingual occurs. In their paper on translanguaging and resemiotization, where the authors follow the creative process of writing a text and turning it into a song performance, Moore and Bradly states that semiotic changes emerge “across, through and beyond practices … involving written and spoken language”. This gesture focuses “on the communicative processes that help bring such transformations about23.”

Image no. 11, Cia Rinne Sounds for soloists, YouTube cover image

Image no. 12, Cia Rinne, Sounds for soloists

40A successful conjunction between bruitist and simultaneous sound poetic forms, Cia Rinne’s sound works combine the individual pronunciation of linguistic elements and their stylistic effects of the languages in which she is highly proficient. The sound designer of Sounds for soloists, Sebastian Eskildsen, reveals his major strategies in shaping the piece in the pdf. image on the next page (Image no. 12). What he writes about the editing of the first lines, is coherently present in the whole work. The text of Rinne goes like this:

notes for two

*

1

one

ohne

oh no

ono

on

o.

(oh no)

41By using pitch shifters to change the spoken pitch of the author, Eskildsen successfully mirrors the key device of Rinne’s translingual poetry, namely homophoning. This homophoning with formant shifter shapes both the “soloists” of this piece, as well as the “sounds” of languages. For accompaniment Eskildesen uses a simple tone generator. The generated sine wave, pink noise and sine sweep and their later modifications in minimalist style bring all kind of associations to decomposing of thought, of sound and voice and through them the decomposition of the whole universe. Listening to this pulling apart of mental and physical pieces by “wars and gods”, the listener—who is part of a static, composed reality—experiences a special tension. In this acoustic tension, hearing the pronounced multilingual words still yield great pleasure, which culminates with the reading of all kind of orthographic symbols that unify these babelic languages (and their orthographies). The illustrative mechanical, urban and human sounds which for first time are broken by sounds of musical instruments (like claves and drums) in the middle of this 14-minute-long work, comes to a head in a digital jam session with a clear ending by a simple technical sound elevating very high.

42With her poetry installations in various art spaces around the world, like Signal Malmö, the Turku Biennial, the Grimmuseum Berlin, Den Frie and Overgaden in Copenhagen, at INCA Seattle, the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn, etc., Rinne is mobilising the spoken, written, visual, printed and digital resources of different languages with three-dimensional spatial representation modes. Evolving from her concrete poetry, the sound poetical works and art installations of Cia Rinne operate not as much with the semantic and syntactic but the phonetic and visual, static and ephemeral aspects of multilingualism.

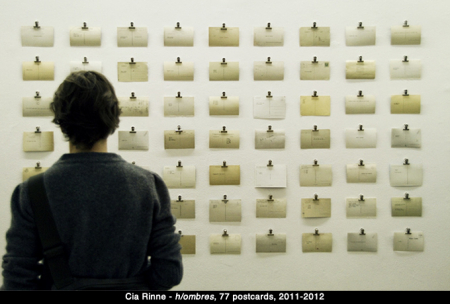

Image no.13, Cia Rinne: h/ombres, Installation

43Both the verbal-figural cards used for installation by Cia Rinne at various exhibitions (see the photo above), or the sound installation Notes for listeners offer their aesthetic pleasures to the audience for a limited time, which will stay with the visitor as a mental memory of an artistic input but not as a concrete image (like with a book) or concrete sound (as on a tape). By addressing such different perceptive senses, the artistic works of Rinne point to poetry and performance as two hypermedialities that can join each other successfully. Just as poetry is capable of incorporating and transforming impulses and elements of all kind of art forms and beyond, performance can also incorporate and use elements originating in other art forms for its own poeticality.

Summary

44The theoretical and methodological goal of this study has been to define the major categories of such artistic play—namely of intralingual, interlingual, intersemiotic and resemiotized translanguaging—and to describe their text-internal as well as intermedial poetic functions. The study also exemplifies how literary translingualism is thematically drafted and enacted as both artistic form and aesthetic procedure in the texts of contemporary artists from different literary traditions. No doubt, such translingual poetics enlarge the horizon of the monolingual literary dominance of the last two centuries; however, the mental and emotional familiarisation of the critics and readers with the multiple codes in an artwork influences the anchoring of such works in the respective literary and artistic fields. Paraphrasing Rinne’s above cited thoughts on conceptual poetry published in Bergvall 2012, one can also conclude that translanguaging and resemiotization are very liberating acts to language as well as aesthetic operating beyond its commonly accepted functions. Although this aspect is not an aim in itself, it is definitely essential to translingual writing.

45 The reduction of a work to its simplest, clearest, most basic structures is typical of minimalism. In employing all four types of translanguaging, Rinne strives for objectivity, schematic clarity, logic and depersonalization, just as in the minimalist art the work refers to. Rinne’s tripartite paradigmatic play lends genuine insight into the laboratory of meaning production of languages along with other media. It also contributes to the structural coherence of the book. This poetic convergence is not simply an iconic mapping of the paradigmatic—it is the creative process itself, generating a unique artistic unity. As Rinne explains in the following passage, while quoting one of the artists that inspired her work the most, Tomas Schmit:

If there is a concern, it is trying to reduce the form to the minimum necessary in order to visualize a thought or idea. Tomas Schmit said in an interview with Wilma Lukatsch that it worked for him like that, “What you can say with a sculpture you do not need to build as architecture, what you can do with a drawing you do not need to search in image, and what you can clear up on a piece of paper does not need to become a huge drawing; and what you can make up in your mind does not even need any piece of paper.” This is something I can fully agree with, the ideal would probably be a constant reduction to almost nothing! In a way it is a countermovement to the massive flood of information and waste of material, too24.

46Rinne’s “idiosyncratic poetic idiom25” has its own rules and laws that provoke dialoguing/translanguaging with the reader from many angles. Just as the artist uses the multilingual and the intersemiotic transgression to free herself from the many conventions and impositions of everyday life, so the reader is invited to experience something similar: his or her own idiosyncrasy. Receivers are allowed to add any “irregular” associations. After all, who decides which meaning the reader may momentarily activate when seeing, for example, the letters N and O? Does it refer to negation or does it indicate geographical locations such as Norway, Lake No in Sudan, New Orleans, or a small village in Denmark? Does it refer to a symbol and abbreviation of a letter/syllable, as in Japanese script? Does it refer to the number sign? Or to a film—as in the 2012 Chilean film by the same name, or the titular character of the James Bond film Dr. No, or to a song—such as those by Shakira, Monrose or Old Man Gloom? Or to a female playable character, as in Koei's “Samurai Warriors” and “Warriors Orochi” video games? Or to a chemical substance (Nitric Oxide) or a chemical element (Nobelium)? Or to political parties (the German neo-Nazi party or a Belgian political party)? Or to a style of Japanese theatre? Or just the two letters his or her child knows?

47 Rinne's visual poetry abolishes the difference between languages, words, images, media namely by transcending them all. However, as Leevi Lehto (2008) has already pointed out, this does not occur in a romantic, transgressive way, but as a critical categorical act. In Rinne’s work we are dealing with not only linguistic and aesthetic categories, but also with philosophical questions that have been addressed many times throughout history. As Lundberg describes this:

The poet is not “guided” by words and their meanings, but rather by certain pre-existent models and ideas, which she seems to be testing against the material (and materiality) of language(s). What she then “discovers” in and between languages, is not “truth” (let alone the “sameness” of languages (“nine” <> “nein”)), but rather a certain inadequacy, a slowness, a resistance from the part of language to “thinking” - so that in the end, one could as well talk about the Primat of language, as in this quote from Wittgenstein, figuring in the book, typically, either as an individual “piece” or one of two stanzas in a page-poem: “Man sollte Abschied nehmen von einer Formulierung wie ‘ich denke’, und statt dessen sagen, ‘dies ist ein Gedanke’ und dann tritt man zu diesem Gedanken in Beziehung26.”

48Rinne’s overall affection for “pre-existent models and ideas” is easy to trace back via Fluxus and concretism to avant garde movements; however, critics rarely reach as far back as early modern art debates or even antiquity. What we find here, are periodical analyses of the matter. The debate over the idea and matter of conceptual art is of course not a new phenomenon. It is more interesting to see through a historical perspective that links the philosophical tradition from Plato and Aristotle with disegno and colore—the art dialogue that occurred during the Renaissance between two Italian cities, the inland Florence and the coastal and more modern Venice. The lasting discourse on disegno and colore revolves around how an idea can become a form, how it can be brought to paper by imagination and drawing. In his art historical reflections on mapping the space René Undusk further outlines the implications of this idea on our modern time:

Its most remarkable continuation took place in the clash of the Rubenists and Poussinists in 17th century France, being indirectly part of the famous querelle des anciens et des modernes, but in fact the argument has played a constitutive role in the jerky process that can be called the formation of the European modernist discourse. Let us recall, for example, the Classicist obsessions with contour of Johann Joachim Winckelmann…, and the respective deprecation of the boundary line in Romantic ideology... Romanticism as a movement built amply on the luminous and visionary perception of landscapes, which deconstructed the distinctively corporeal aspect of the picture, or at least balanced it with the painter’s attempt at a unitary effect in the work. These efforts to grasp the essence of painting in terms of colour were articulated explicitly in German Romantic theory, where modern art was equated with pittoresk and Kolorit, while sculpture was considered ancient and relevant to Zeichnung27.

49Of course, it is not my intention to examine the vast material on this subject, but rather to pinpoint these historical events and their potential to offer new insights into contemporary visual poetry/art. The above included translingual literary works manifest special strategies mapping the multilinguality of our world, which gained special actuality in societies at the beginning of the 21st century. By adding the visual, acoustic and spatial elements to translanguaging, Cia Rinne managed to point our solutions of artistic incorporation of multiple communication channels. In this postmodern minimalist fusion of artistic as well as global communication, translanguaging can manifest itself as an aesthetic device that connects traditional and media arts, as well as users of all kind of languages, rather than—as we are used to think—separating them.