Indigenous Discourses of Tornado Risk in Oklahoma

1Discourses of tornado risk are part of everyday life in many parts of the U.S., but can take on different forms. Larry Danielson described how tornado stories in Kansas, a state with the second highest annual frequency of tornadoes, are commonplace in contemporary oral tradition and play a significant role in communicating and dealing with tornado risk1. The research that I have done2 and with colleagues3 shows that the same holds true in neighboring Oklahoma.

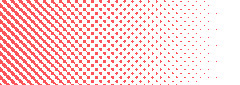

2In Oklahoma, perhaps uniquely due to its history, a particular type of tornado knowledge is based on Indigenous cultural understandings of the natural world. Oklahoma is home to 39 federally-recognized tribes and nations (see Figure 1), making it unique in the United States. And, Oklahoma is home to a vigorous tornado season each year (fourth highest annual frequency), with April and May being the main months of occurrence, although they can happen at any time. As such, tornado discourses are common in Oklahoma, and like Kansas become available for analysis as part of our discussion of natural catastrophes.

Figure 1: Oklahoma and Indian Territories with tribal locations.

Credit: Kmusser, based on 1890s data/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA.

3Tornado discourses come from different cultural and social trajectories. One trajectory includes the local, vernacular knowledge people acquire from having lived in a place for a period of time. This is an observational and sometimes cultural knowledge that provides a situational awareness from having experienced weather in a particular place. Another trajectory includes the scientific knowledge that is produced by tornado experts and then represented and communicated to the public as truth and as actionable information (media coverage, public announcements, warnings) by members of the local media.

4This chapter primarily draws upon my field work during 2008-20114 with Indigenous farmers, ranchers, gardeners, elders, and traditionalists in southwestern Oklahoma on how they conceptualize weather and climate, including the tornado, the focus here. Field work included interviews and participant-observation activities (meetings, workshops, vegetable judging fairs, museum visits) with members of several southwestern Oklahoma tribes (including Kiowa, Apache, Comanche, Wichita, Caddo, Delaware). This field work was prefaced by historical and archival research I conducted, some of which is described here as context.

Indigenous knowledge of the tornado from historical and archival research

5The historical and archival research on Indigenous weather and climate knowledge, including the tornado, revealed observational and belief systems I later heard in the contemporary field setting; this is documented variously in Peppler5. Some examples relevant to the tornado are repeated here6. Maddux related how the Cheyenne and Arapaho people told the first European settlers of Woodward, Oklahoma in 1893 that tornadoes would not track along the nearby North Canadian River7. This was said to lead to a false sense of security amongst white settlers in the years leading up to the disastrous 1947 Woodward tornado, with deadly consequence. Maddux, citing historian Wilbur Sturtevant Nye, related the native belief that the tornado had demonic origins8. Tingle’s book of Choctaw Nation stories relates, in “Brothers”, how Joseph split a tornado in half by flinging a hatchet to the ground, causing the tornado’s two split parts to miss the town’s church9. Hale’s volumes on the oral traditions of the Western Delaware of Oklahoma10 contain numerous stories about the weather, including one on preventing tornadoes by holding an axe up toward the wind to break up the cloud, or by burning cedar to keep the wind from coming11. Bierhorst (1983) provided an account of how the Cherokee frightened away storms12. Pybus wrote extensively about what she termed “Native American tornado mythology13”. In all of these, a spiritual connection exists between the people and nature.

6The Doris Duke Collection of American Indian Oral History, part of the Western History Collections at the University of Oklahoma, contains typescripts of weather stories, including about the tornado, as told by tribal peoples in Oklahoma from interviews recorded during 1967-197214. Among stories relevant here, are those from the Cherokee and the Muscogee about burning turtle shells or wrapping and hanging turtle shells in a window to keep tornadoes away.

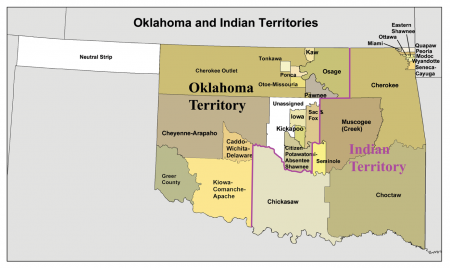

7Some of the most famous of these Indigenous spirit connections to the tornado, in the animistic15 embodiment of the horse, come from the Kiowa Tribe, as described by Momaday16, Greene17, Marchand18, and others, including a Kiowa man interviewed as part of the Duke Collection. Momaday’s recollections of his Kiowa upbringing in The Way to Rainy Mountain (see photo of Rainy Mountain in Figure 2) include the story of the Storm Spirit, including the passage:

Even now, when they see the storm clouds gathering, the Kiowas know what it is: that a strange wild animal roams on the sky. It has the head of a horse and the tail of a great fish. Lightning comes from its mouth, and the tail, whipping and thrashing on the air, makes the high, hot wind of the tornado. But they speak to it, saying ‘Pass over me’. They are not afraid of Man-ka-ih, for it understands their language19.

Figure 2: Rainy Mountain in southwestern Oklahoma, November 2020.

Figure 2: Rainy Mountain in southwestern Oklahoma, November 2020.

Photo by R. Peppler.

8Greene described the works of Silver Horn (Haungooah), a Kiowa who recorded events and time in pictorial calendars. Some calendars include references to the tornado. The “Great Cyclone Summer” pictorial20 coincided with the tornado that destroyed the town of Snyder on May 10, 1905 – more than 100 people lost their lives in this tornado, still considered one of the deadliest on record in the U.S. The image drawn represents Red Horse, the supernatural storm maker who has the upper body of the horse and a long sinuous tail “like a snake” – it whips around the tail “to stir up tornadoes”, a description similar to Momaday’s Storm Spirit. The 1905-06 “Red Horse Winter” represents a tornado that hit Mountain View, Oklahoma, on November 4. That storm was described at the time as “second only to the great Snyder disaster last spring21”. The calendar for the summer of 1912 is particularly relevant as it depicted several winged horses, signifying how Red Horse visited Kiowa territory repeatedly that spring and summer22. A small tornado was depicted as Red Horse shaking his ears, while a large tornado was depicted as many horses running. A small tipi in this pictograph, belonging to Silver Horn’s brother, Charlie Buffalo, is shown with a group of people gathered around it. It was said that people would gather around “Grandpa Buffalo” during a storm “as he had the power to make it pass safely by23”.

Indigenous knowledge of the tornado from field work conversations

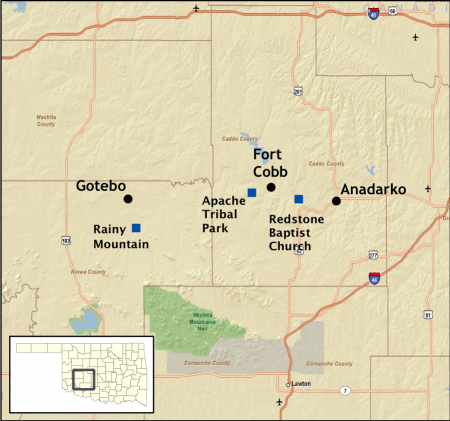

9Many of the farmers, ranchers, gardeners, elders, and traditionalists I spoke with (see Figure 3 for locations of primary conversation locations) explained that while they consult modern weather and climate information to help guide their farming decisions and daily activities, they prize their own observations and indicators as local relevance and situational awareness that cannot be obtained from other sources. My field research suggested, as has other much other research with Indigenous communities, that the observational and performative ritual components of their knowledge are deeply rooted in a belief system that promotes an intimate, reciprocal relationship with the spirit-imbued natural world, and in many cases is informed by stories and actions passed down from family members24. This knowledge represents culturally situated and placed based “ways of knowing” that are subject to mediation through various social and group influences. The observational and performative aspects of this knowledge are practiced and renewed routinely and adapt and evolve over time, and more importantly for this contribution, are invoked during times of pandemonium such as an approaching tornado.

Figure 3: Field work locations in southwestern Oklahoma.

Credit: William G. McPherson, Jr. for Peppler (2012) using ArcGIS Online. 2009 Esri, TomTom, AND.

10Several conversations described using sharp objects to make it split, corresponding to the stories from the past described in the previous section. A Delaware man, Larry Snake, told about how his grandmother could split storms. She would walk outside when a storm approached and pray to it. She would either hold a knife high or place it in the ground, in both cases with the sharp edge facing the storm, in order to cut the storm in half and make it go around their property. According to this man, this action always worked. Another man also talked about the Delaware and Wichita method of using a butcher knife to split a storm. This person said you hold up a knife to the storm and then cast it into the ground, and he had performed this rite as a precautionary action every spring except for one, 2009, when Anadarko experienced a tornado. This person’s comment was, “Who knows!” when asked if he believed this works. A Kiowa woman and traditionalist, Maya Torralba, told me she had also heard people say that a Caddo or Wichita way to ward off the storm is to put a hatchet into the ground, and the storm splits and goes in two directions. She said, “You are supposed to point the blade toward the storm. I’ve heard of a Creek family that uses the same (hatchet) method”. A Kiowa farmer, Rickey Horse, related a similar story about how his Kiowa grandmother would talk to an approaching tornado and throw a hatchet into the ground to split it.

11A female Kiowa elder and traditionalist, Dorothy WhiteHorse DeLaune, provided a detailed account of how the old people split storms. She said:

I’ve seen my elders know when the weather was going to get bad – we had no radio, no nothing, no way of communicating. They also knew how to stop a tornado that would be coming. The practice went to my brother. Grandpa would tie a handkerchief in four knots and go out to the back, and a lot of the Kiowas will tell you their grandmothers or their grandfathers had done that. They go out to the back. In those days too all of the weather came from the northwest or the southwest. Now the tornadoes are hitting from the north, they’re hitting from any direction. That’s just not what the Indians believed in the old days. They’ll say, ‘Oh it’s okay, it’s in the north it’s going away.’ Now, this [May 13, 2009] tornado that hit this place [the museum] came from the north. It was uncanny – because they’d either take a hatchet, a little hand hatchet, or a knife, a butcher knife we called those, and go out to the back of the house. And all of the Kiowas called that cutting the clouds – you prayed to the Spirit and you say ‘Go to where there are no people, don’t hurt anybody’. I’ve heard some of them even call the clouds ‘Brother’ – ‘You’re not here to destroy people, we’re poor.’ Those are prayer words. Sure enough the clouds would pretty soon dissipate – I’ve seen it happen. Anybody my age or around that era will say ‘Oh yeah, grandma used to do that, too.’ I don’t know the ritual – I should have went out there and watched.

12Stories about praying to the tornado to make it pass over or split were also told. A Kiowa farmer and teacher, Randall Ware, described how his grandfather talked to the storms to split them in half, echoing the passages written by Momaday and others about how the Kiowas spoke to storms. He elaborated:

Our elders knew how to talk to the storms to make them move and all that – they were really religious people. They really relied heavily upon God to hear their prayers and everything. I stand here as a personal witness to it. I saw it happen. A tornado was coming to our home like that, we had my grandfather and uncle there, and they went outside and talked to the storm and it missed us. It was coming dead at us. He (grandfather) was standing there, and it was a strong faith to talk to the storm to miss us. Occasionally it split, too. Unbelievable. A lot of these things we see first‑hand.

13Maya Torralba provided two poignant accounts of her ability to talk to storms to make them pass. Of this ability, she said,

I can feel when a storm is coming and feel how strong it’s going to be – I know that’s weird, I know that’s not scientific or anything, but I don’t understand how I can feel that way having not been here my whole life. Now I can understand an elder that’s been here their whole life – they know storms are because they’ve been here and they know the patterns.

14“My husband asks ‘What’s it gonna do?’ Well, I don’t really know but I have a feeling – it’s probably going to split as it comes this way and it usually does.” She continued, “When we see severe weather coming we usually will pray – my husband (who is Comanche) goes out with tobacco and says a prayer. Then he takes the tobacco and offers it to the storm in the direction it’s coming from, and asks for it to pass over us. And it does”.

15She described two specific events when she prayed to have the tornadoes pass without harm – the May 13, 2009 tornado that hit the east side of Anadarko, and the May 19, 2011 storm that produced a brief tornado between Fort Cobb and Anadarko nearer her home. She offered a detailed account of how she talked to the May 13 storm in Kiowa:

It was an odd storm because it came from the northeast. That was odd, and threw me off totally. I kept seeing things dropping and said this is not right. The [television] stations said ‘There is no rotation, there’s nothing here’ and I said that’s not right, wait a second. Something isn’t right here, and then the power went out and the wind started blowing. We saw that straight-line wind, we were definitely feeling that, we could feel it on the roof. When we were praying, we took the mattress out. We have a storm shelter very close to our house, a community storm shelter, but we had no time when that wind started blowing and debris started blowing straight south. We had no time to get in there so we put the mattress over the kids. As we started praying, we spoke Kiowa to the tornado because that’s what our ancestors used to do and that’s what my grandmother used to say. And some of my aunts told me this is what you’re supposed to do. And I got a text message from my cousin saying ‘There’s a tornado coming – talk Kiowa, talk Kiowa!’ – she kept saying that. And I said well where is it and she said ‘It doesn’t matter, just start talking Kiowa!’ So we started saying [in Kiowa] ‘I’m Kiowa’, or ‘Do you recognize us, we’re Kiowa?’ I know about storms, and I’m an educated person, but at the same time I knew that this is something we needed to do and use that tradition. And even saying that calmed the family down, calmed my kids down. They felt like they had power to say something, power and control over that storm, and they calmed down. At that point, when it got really, really strong, I felt a hand come on my back and just push me down over my kids and my husband. It was the weirdest thing – I thought ‘Do I fight this?’ No, it just pushed me over and I just put my hands over them and we just all started praying and speaking Kiowa. And then we could hear a train going far away – that’s it (the tornado), going east of us. As we kind of calmed down a little bit and you could still feel the wind – it wasn’t as strong but pretty strong still. My brother called me and I said it’s already passed, and he said ‘Yeah they’re saying it’s passed, it’s on the east side of town. But what if there’s other rotations you don’t know about? You need to get to the shelter.’ So, we each took a twin, my husband and I, and I grabbed our oldest and we ran. As we ran I looked up and I could see this huge white wall – it was this massive white wall to the east of us – and that was the straight line winds you were talking about – it was just huge, like you could touch it. It was pretty scary. So we just ran into the shelter and waited.

16About the May 19 storm, which was confirmed to have touched down near the Redstone Baptist Church (see Figure 4), she said:

Yes. We have no sirens, but we were listening to the TV and watching the skies. We had just returned from Fort Cobb Lake. There was so much rain it was hard to spot. But once I saw the inflow, I knew. Although it was small, I made my family get into the shelter. We also helped an elder and neighborhood kids get into the shelter. I stayed above to watch, and to speak Kiowa to the storm. It worked! The tornado went back up just a half to quarter mile west of the house and was trying to drop again, right over our backyard. That was when I took the picture. Talk about a crazy way to start the summer!

Figure 4: Conversation site, community garden at Redstone Baptist Church, June 201025.

Photo by R. Peppler.

17Finally, a few farmers talked about the increasingly unpredictable nature of tornadoes (Dorothy WhiteHorse DeLaune touched on this as well) due to climate change26, adding another dimension to the tornado discourse. A younger Kiowa farmer, Dixon Palmer, told me:

Last year is totally different from this year. It’s all changing. It used to be winter would get cold and you’d have a snow, springtime it would be wet, summertime would be summertime. Now they’re having tornadoes in the fall, everything is starting to mix up, the weather is changing, the atmosphere is changing. And it’s hard to deal with stuff like that anymore. It isn’t like it used to be.

18Another Kiowa farmer and traditionalist, Richard Tartsah Jr., commented similarly, saying: “Years ago there was like a set pattern—tornado season was from March to May. But now it’s just anytime. It just doesn’t give you time to react anymore.” Some suggested that recent extremes of weather and climate are signs from the natural world that it is unhappy with our treatment of it, and that we need to mend our ways. As was told to me, if you treat nature well, it will give back to you in a positive way (such as through a bountiful crop), and if you do not treat it well, there could be consequences (such as severe weather like tornadoes happening out of season).

Indigenous knowledge as an alternative cosmology of the tornado natural catastrophe

19While everyone I talked to consults scientific weather information, many still privilege their own local observations and the insights they gain from them – they see this as a situational awareness, an intuition, a place-based wisdom nested within a belief system that suggests humans should possess a closeness and intimacy with the spirits in the natural world and should exercise respect and reciprocity when engaging with it – all things they cannot get from opening the computer or turning on the television. This also represents a connection with their past.

20A Comanche rancher, Milton Sovo, told me that he has had a lifelong interest in weather because as a child a tornado came up the creek near his house as it hit the Walters, Oklahoma area. He explained, “My weather knowledge is self-taught – like say from the time I went through that experience, and I began to find books and find other articles about weather”. While he heavily values his own knowledge, he still consults scientific weather information, “I want to see real-time weather”, he said. “I look at the radars a lot, the satellite pictures a lot. I try to watch Channel 9 and Channel 4 [in Oklahoma City].” He also consults the Oklahoma Mesonet data online. He saw the May 3, 1999, tornado when it first formed near Elgin, Oklahoma. “That’s when we really started watching it [television weather].” His son-in-law in Arkansas showed him a weather app for the phone that he decided he would buy. “It’s just like $4 a month – it’s worth it to me because I have to know what the weather is up here. I live in Elgin and by the time I get to Indian City [Anadarko] I run into ice, so I need to know what it is up here.” He admitted, “I honestly and truly feel like up until oh, I’d say seven years ago, about the time they started using Doppler [radar] regularly, I could always out-predict the weather stations. But after Gary England [famous Oklahoma television meteorologist] got the Doppler then he had the best, when they started seeing inside the storms, then they were doing better than I was”.

21This Indigenous tornado knowledge system can be considered similar in some ways (minus the performative elements to disrupt storms) to the local, vernacular knowledge of weather that is often termed as folklore or folk science and possessed or observed by peoples of all ethnicities and cultures in many different places.

22For example, from Klockow et al. for Alabama and Mississippi27 and Peppler et al. for central Oklahoma28, our interviews and town hall discussions with local people revealed beliefs about tornado risk are rooted in local life experiences in particular places. Some people felt they were protected from tornadoes by hills or a waterway, or were left unprotected by a new highway being built that required portions of forests to be removed. People characterized their risk to tornadoes in terms of the probability of a tornado striking a relatively small area based on their own experience-based tornado climatology that they have developed from living in that place for a period of time. These personal climatologies turn out to be quite accurate.

23Such Indigenous and local perspectives may differ fundamentally from the professional meteorologists’ understanding of tornadoes being formed by physical and thermodynamic processes within a vast atmosphere cauldron, and that the distribution of tornadoes is mostly random albeit within in favored tornado alleys. This difference in tornado epistemology has been called out by scientists who wish to identify and dispel what are considered local tornado myths. Indeed, the U.S. National Weather Service has written about this in service assessments such as after the major tornado event in Alabama and Mississippi. In that assessment, it describes weather myths as “preconceived notions based on local, often erroneous, information regarding weather threats”. The assessment team for the event then noted that meteorologists should “consider identifying and dispelling local myth” as in its opinion such myths act as a “barrier to personalizing the threat”29.

24In the end, this study showed that there are different ways of characterizing the awesome natural force of the tornado catastrophe and personalizing its risk, including as described here in Indigenous ways. All such discourses have value in some way or other and should not be discounted, as we try to understand how people recognize their risk to the tornado. Randall Ware once told me, “These things need to be preserved. There needs to be more teaching”. As Jason Baird Jackson stated when commenting on Greene’s Silver Horn volume30, “My point is simply to reaffirm the fact that Americans have a diversity of perspectives on the world and that Native perspectives are still too-rarely acknowledged to even exist, let alone to be understood meaningfully and seriously31”. Adrian Baker states this notion well in the prefaces to his Injunuity film series pieces32, which begin with, “In a world searching for answers, it is time we looked to Native wisdom for guidance. It is time for some…”